VIII: Hugo Herrmann – Seraphische Musik für Klavier, Ludus sopra antiphonae "In paradisum" (1951)

Please select a title to play

I: Hugo Herrmann – Sonate für Violine und Klavier op. 17 (1925)

I: Hugo Herrmann – Sonate für Violine und Klavier op. 17 (1925)I: Hugo Herrmann – Sonate für Violine und Klavier op. 17 (1925)

01 Fließend, quasi andante

I: Hugo Herrmann – Sonate für Violine und Klavier op. 17 (1925)

02 Preludio, larghetto con molto espressione

I: Hugo Herrmann – Sonate für Violine und Klavier op. 17 (1925)

03 Vivace quasi scherzando

II: Hugo Herrmann – Toccata gotica für Klavier op. 16

04 Toccata gotica

III: Hugo Herrmann – Invocation für Klavier op. 18b Nr. 1 (1925)

05 Invocation

IV: Felix Petyrek – 6 Griechische Rhapsodien für Klavier (1927)

06 Athen

IV: Felix Petyrek – 6 Griechische Rhapsodien für Klavier (1927)

07 Euboia

IV: Felix Petyrek – 6 Griechische Rhapsodien für Klavier (1927)

08 Klagegesang

IV: Felix Petyrek – 6 Griechische Rhapsodien für Klavier (1927)

09 Der Tanz um das hölzerne Pferd

IV: Felix Petyrek – 6 Griechische Rhapsodien für Klavier (1927)

10 Delphische Rhapsodie

IV: Felix Petyrek – 6 Griechische Rhapsodien für Klavier (1927)

11 Serenade der Räuberbande

V: Leon Klepper – Deux Danses pour piano (1932)

12 Deux Danses Nr. 1

V: Leon Klepper – Deux Danses pour piano (1932)

13 Deux Danses Nr. 2

VI: Isco Thaler – In the Rabbi's Court für Klavier

14 In the Rabbi's Court

VII: Isco Thaler – Sabbath's End für Klavier

15 Sabbath's End

VIII: Hugo Herrmann – Seraphische Musik für Klavier, Ludus sopra antiphonae "In paradisum" (1951)

16 Präambulum

VIII: Hugo Herrmann – Seraphische Musik für Klavier, Ludus sopra antiphonae "In paradisum" (1951)

17 Evocation

VIII: Hugo Herrmann – Seraphische Musik für Klavier, Ludus sopra antiphonae "In paradisum" (1951)

18 Pastorale in paradiso

Twenty years have passed since the release of the first CD in the series Franz Schreker's Masterclasses in Vienna and Berlin – a long period in which the works of many of Schreker's pupils have gradually received wide recognition after decades of being forgotten and suppressed. When in 2000 the CD series was inaugurated with the piano music of Felix Petyrek (EDA 17), one of the most eminent and in his time most famous of Schreker's pupils, research into Schreker's Berlin composition class, which in German-speaking areas was unique in terms of its musical diversity, was still in its infancy. After the downright spectacular rediscovery of Berthold Goldschmidt in the 1990s, there appeared in 1998 both Ernst Krenek's autobiography Memoirs – a posthumously edited, extraordinarily detailed compendium full of spite and malice toward most of his one-time companions – as well as Lisa Mahn's biography of her former teacher (and Krenek's fellow student) Felix Petyrek. This was followed two years later by Barbara Busch's seminal book on Berthold Goldschmidts Opern im Kontext von Musik- und Zeitgeschichte (Berthold Goldschmidt's Operas in the Context of Musical and Contemporary History) and Martin Schüssler's work about Karol Rathaus. The sonic realization of this music has since taken place largely thanks to a number of CD productions; in concert life, however, works by these Schreker pupils, who attained prominent status in the musical life of the Weimar Republic, are seldom encountered.

With the lexicon Franz Schrekers Schüler in Berlin (Franz Schreker's Pupils in Berlin), published in 2005 by Dietmar Schenk, Markus Böggemann, and Rainer Cadenbach, a compendium was finally presented, seventy-one years after Schreker's untimely death, that not only documented the lives of all of his pupils from the period of his teaching activity in Berlin between 1920 and 1933, but also aspects of their relationship to Schreker, and the whereabouts of their legacies. We explicitly refer to this fundamental source with regard to the biographical information about the composers on the present CD.

This CD thus brings together works by composers who, with the exception of Felix Petyrek (who studied with Schreker in Vienna between 1912 and 1919), received substantial impulses nearly at the same time in the early 1920s at Berlin's College of Music (Hochschule für Musik). However, their biographies could hardly be more different: Hugo Herrmann and Felix Petyrek, both prominent personalities in the modern music scene in Germany of the 1920s, each stumbled after 1933 in a different way into the machinery of Nazi cultural politics. The two Schreker pupils probably met in person on 3 May 1932 at the latest during the Pfullinger Kammermusik festival (1931–1933), which had been founded by Herrmann, on the occasion of a piano recital given by Else Herold with works by Petyrek and Herrmann (Toccata gotica op. 16). They lived concurrently in Stuttgart from 1935 to 1939, the year of Petyrek's appointment to a professorship in Leipzig. Of Jewish descent, Leon Klepper and Isco Thaler found exile in Israel – for Klepper this was however only temporary: after five years in Jerusalem, he left in 1965 to take up residence in Freiburg im Breisgau.

Hugo Herrmann's Sonata for violin and piano op. 17, from 1925 opens the program: in spite of its traditional three-movement form, it is a markedly experimental work that intensively reflects both the impressions that Herrmann was able to gather from Schreker during the winter of 1922/23 in Berlin as well as the experiences from his time as an organist in Detroit between 1923 and 1925. Striking in the free-tonal, floating first movement are numerous moments of minimalist rotation of tiny groups of tones that are confronted, as a larger contrast, with a nearly expressionistic, space-consuming individual gesture of the two instruments. With all its composed stylistic breaks, this movement is reminiscent of works by Charles Ives, whose avant-garde musical language Hugo Herrmann had possibly become acquainted with during his two-year sojourn in the USA. Remarkable at the end of the movement is the tonal blend of the two instruments, which until then are led side by side in strict linearity: in the last ten measures, the violin and piano join in a continually expanding, ecstatically entwining bitonal chord consisting of C Major and E-flat Major (as a seventh chord) – a harmonic scenario typical of Schreker as, for example, in the prelude to Die Gezeichneten (The Stigmatized). Herrmann fashions the slow movement in a highly unconventional manner as a somber-emotional lament for the violin alone, as a suspenseful Preludio to the immediately following final Rondo, which is in turn determined in terms of timbre by the rhythmically and metrically individually informed linearity of the violin and the piano. The result here, as in the first movement, are moments of extreme harmonic confrontation that gradually transform in the Coda, above the piano's C pedal point, into a joint C Major in the violin and piano.

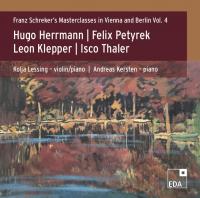

In a biographical profile of Hugo Herrmann in the Neue Musik-Zeitung 49, no. 14 (1928) is found the following characterization of his early choral works: "polyphonic worlds in which archaizing sensibility, the ancient art of organ mixture, and Busoni-Schoenbergian stylistic goals are variedly reflected." Even after ninety years, these words have lost nothing of their validity; they can be applied just as appropriately to Herrmann's three disparate early works from 1925/26 presented here, works that reveal this composer's extraordinarily multifaceted range of expression. While the title of the Toccata gotica op. 16 (dedicated to Wilhelm Kempff) is a reference to Busoni's essay Die "Gotiker" von Chicago, to his acknowledgment of Bernhard Ziehn and Wilhelm Middelschulte, who devoted themselves in Chicago to a harmonic revival of the ancient Central-European polyphonic tradition, this highly segmented work proves to be a brilliant organ-inspired virtuoso piece. Contrasting with this is the hitherto unpublished Invocation op. 18b no. 1, a notturno (as Herrmann called it in a later work catalogue) composed in July 1925 and inspired by the picture Herbstwald am See (Autumnal Forest on the Lake) – reproduced on the cover of this CD – by the dedicatee and friend, the painter Fritz Sprandel. In this miniature, Hugo Herrmann shows himself to be a tone poet whose melodies and harmonies suggest a certain affinity to the music of Alban Berg.

As one of the pioneers of modern music in Germany and additionally as the composer of the opera Vasantasena on a libretto by Lion Feuchtwanger, which was successfully premiered in 1930 in Wiesbaden, Hugo Herrmann was initially considered a creator of degenerate music by the Nazis, a verdict that he escaped in a life-saving, yet questionable manner: through his arrangement of the vile Horst-Wessel Song for accordion, an instrument he propagated for concert use, as well as through his subsequent joining the Nazi party in 1939, from which he however resigned in 1944. In spite of this blemish, Herrmann numbers – as composer, choir conductor, pedagogue, and founder of numerous festivals for modern music – among the most interesting and versatile artistic personalities from the first years of Schreker's teaching activity in Berlin.

During the early years of his career, Felix Petyrek, like most of his fellow students, stood under the stylistic influence of his teacher, from whom he was able to emancipate himself musically to some extent in the early 1920s by means of sarcastic humor. His Irrelohe Foxtrott for piano (EDA 17) represents an eloquent example for this separation process, a bitingly witty parody of Schreker's opera of the same name. Petyrek's diverse activities in the 1920s as a composer in all genres, as a pianist for modern music, and as a passionate pedagogue were substantially informed by the search for a central point, a search that ultimately led him in 1926 to Athens for almost four years. As professor of piano at the Athens Conservatoire "Odeon", Petyrek received in the first months – after his arrival in the Greek capital city on 2 November 1926 – fascinating impressions of a culture that was entirely foreign to him. The encounter with ancient Byzantine scales as well as with the magic of archaic folk festivals and rituals inspired Petyrek to compose the Six Greek Rhapsodies about whose genesis he reported to his friend, opera librettist, and patron Hans Reinhart on 1 June 1927: "In late May, I wrote six Greek piano pieces, a rather new style employing the indigenous scales and formal principles. Some people have called them my best works. I would like to have them printed right away." In fact, these Six Greek Rhapsodies, which Petyrek premiered already on 20 August 1927 in a piano recital in Dornach (Switzerland) and which were published by Universal-Edition Vienna in 1929, represent, together with the Third Piano Sonata (EDA 17) from 1928, a pinnacle in Petyrek's extensive œuvre. Not only in their harmonic originality beyond the European major-minor system and their rhythmical energy marked by shifting meters do these rhapsodies vividly reflect atmospheres, scenarios, and legends of Greek life – also in terms of timbre, Petyrek fathoms all the extremes, namely the darkest registers of the piano (conclusion of no. 2 Euboia, no. 3 Lament, the beginning of no. 4 The Dance around the Wooden Horse), he additionally again and again employs cluster-like effects and rapid tone repetitions (in no. 3) which immediately allow their inspiration from various percussion instruments to be recognized. With stylistic refinement, Petyrek expands in the first part of the Dance around the Wooden Horse the initially two-part texture fashioned completely independent of the two voices into a four-part juxtaposition of metrically entirely different sequences. In all the rhapsodies – with the exception of the last – this complexity of texture stands formally opposite a clearly comprehensible tripartite form, partially segmented by long pauses, based on the A–B–A model.

It is a part of the tragedy of Petyrek's life that soon after his return to Central Europe – in 1930 he was appointed professor at the Stuttgart Hochschule für Musik as successor to Wilhelm Kempff – ran afoul of the Nazis' "cultural policy": as a composer performed at numerous modern music festivals in the Weimar Republic and additionally as a member of the leftist-oriented "November Group", he could not help but attract the Nazis' attention in 1933 with works such as the Greek Rhapsodies and many others from the 1920s. The continuation of his professorship in Stuttgart was contingent on his joining the NSDAP. Later plans to emigrate to Switzerland came to naught. Most of Petyrek's avant-garde compositions from the late second decade of the twentieth century to the early 1930s thus disappeared from concert programs; only the past two decades have seen a gradual rediscovery of this fascinating musical cosmopolitan.

The raucous, to some extent ecstatically unfettered virtuosity of Peytrek's Greek Rhapsodies with their characteristic oriental colors correspond in an almost surprising manner to the Deux Danses composed only five years later by the Romanian Leon Klepper. Rapid, extreme changes of register, bitonal clashes, and melismatic melodies repeatedly marked by augmented seconds inform the two tonally – in modal C minor – closely interlinked dance movements, which display folkloric as well as jazz-inspired influences: especially the wild conclusion of the first piece comes across like a pianistic apotheosis of the jazz of the late 1920s, quasi an orgiastic dance on the brink of the abyss. None other than the fifteen-year-old Dinu Lipatti premiered the Deux Danses in 1932. While Leon Klepper's life and work took place in the artistically multifariously inspiring field of tension between Germany (studies with Franz Schreker and his return later in life), France (studies with Paul Dukas), Romania (professorship in composition), and Israel, the traces of his fellow student Isco Thaler vanish in the young state of Israel. Far too little is known about this Galician composer, whom Ernst Krenek retrospectively characterized in his autobiography Memoirs: "a picturesque and quaint Jewish boy, who was very reticent, so that he seemed haughty and arrogant, and worked extremely slowly, grinding out in weeks not more than one or two bars of a music that seemed absolutely incomprehensible." The latter attribute, however, is eloquently belied by the two piano pieces In the Rabbi's Court and Sabbath's End issued in 1950 by a small Israeli publishing house: intimate miniatures infused with sacral magic, whose melodic material reveals the close proximity to traditional Jewish melodies. The monodic beginning of the first piece is thus reminiscent of a cantor in the synagogue – and at the same time of the opening bars of Schreker's opera Der singende Teufel (The Singing Devil), which was premiered in 1928. In both pieces, each in tripartite form, the polyphonically fashioned harmonization in tiny chromatic steps of the main melodic voice is fascinating. Alongside the pieces that Isco Thaler wrote for the violoncello method by his friend Joachim Stutschewsky – who in turn dedicated his Three Pieces for Piano from 1941 to Thaler – these two miniatures represent the legacy of a composer whose biography and works, beyond the years of study with Schreker in Berlin in 1920–1923, remain entirely in the dark.

In 1951 Hugo Herrmann wrote the Seraphic Music – Ludus sopra antiphonae "In paradisum", a kind of credo by the devout Catholic, who recorded it in 1952 and 1954 for the South German Radio (SDR) Stuttgart and Bavarian Radio (BR) Munich, respectively. All three movements are based on the Gregorian chant "In paradisum". Additionally, in the second movement, Evocation, the dramatic climax of the triptych, the B–A–C–H motif appears in various transpositions, ultimately also in the original form. Far from all stylistic classifications, a music that reveals itself in the Präambulum seems to arise as out of a long existing, yet inaudible motion – an archaic polyphonic architecture of sublime expanse of space which once again is reminiscent of Busoni's acknowledgment of Die "Gotiker" von Chicago. In this triptych, Hugo Herrmann creates a world of sound that counters the breakneck pace of the rebuilding in West Germany after the apocalypse of 1945 with a radical pause, a meditation in harmonies that transcends the traditional categories of consistency and dissonance. Abrupt contrasts of dynamics and tonal registers mark the Evocation that constantly intensifies to new ecstatic, nearly menacing eruptions, which ultimately die out in the softest somber colors.

Pastorale in paradiso takes recourse to the models of motion of the Präambulum, transforming it however into ritual-like perpetual ostinatos that are simultaneously joined in different speeds by the actual cantus firmus. In this way, a magical, quasi minimalistic continuum develops, allowing astonishing harmonic constellations to emerge. Like the previous two movements, the Pasatorale in paradiso also dies away in an explicitly indicated morendo. As the highest individual sounding attestation of an avowed Catholic, the Seraphic Music belongs to a tradition of religious-inspired piano works that ranges from Liszt to Messiaen, at the same time combining retrospective impressions of the old and new worlds into a fascinating synthesis.

I would like to thank most cordially Dr. Andreas Fallscheer-Schlegel for his manifold support of this CD. Special thanks to Prof. Dr. Friedrich Frischknecht for the permission to use Fritz Sprandel's painting Herbstwald am See for the cover of this CD and to Daniel Lienhard for the rare portrait of Leon Klepper.

Kolja Lessing (engl. Übersetzung: Howard Weiner)

March 2020