III: Karol Rathaus - String Quartet No.5 op.72 (1954)

Please select a title to play

I: Ignatz Waghalter - String Quartet D Major op.3 (ca.1900)

I: Ignatz Waghalter - String Quartet D Major op.3 (ca.1900)I: Ignatz Waghalter - String Quartet D Major op.3 (ca.1900)

01 Allegro Moderato

I: Ignatz Waghalter - String Quartet D Major op.3 (ca.1900)

02 Allegretto

I: Ignatz Waghalter - String Quartet D Major op.3 (ca.1900)

03 Adagio ma non troppo e mesto

I: Ignatz Waghalter - String Quartet D Major op.3 (ca.1900)

04 Allegretto con Variazioni

II: Ignace Strasfogel - String Quartet No.1 (ca. 1927)

05 Adagio

II: Ignace Strasfogel - String Quartet No.1 (ca. 1927)

06 Allegretto

III: Karol Rathaus - String Quartet No.5 op.72 (1954)

07 Allegretto con moto

III: Karol Rathaus - String Quartet No.5 op.72 (1954)

08 Largo

III: Karol Rathaus - String Quartet No.5 op.72 (1954)

09 Allegro vivace

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This CD has been awarded the German Record Critics Award and was included in the Bestenliste 4/2019.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

"One should be undaunted in presenting oneself as a good European, and work actively on the merging of nations: whereby the Germans, owing to their trait of being the nations' interpreter and mediator, will be able to help."

Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All too Human, 1878

"I cannot believe – in spite of all knowledge – that life in this country, which was the most European of all countries, will not be tenable any more. For someone who ... aspired to work according to the spiritual principles of life and art, for someone who for precisely that reason was linked to German intellectual life so closely and in such a special way. Perhaps it was a coincidence that I was able to establish myself in Germany, and nearly only in Germany. I attempted it invariably with my merits. I was never compelled to take detours, I never needed to make use of social connections. Is this success only by means of the works even conceivable anywhere else?"

Karol Rathaus to his publisher Hans Heinsheimer, 1933

"Before my departure I contrasted the present-day Berlin with the city I had known earlier. The splendour of the streets, the unparalleled luminosity and joie de vivre and the special glow of the Berlin sun had all darkened. No longer is one fascinated in Berlin by pure art, music, literature or science. The only ideal for the young of both sexes is the constant marching, which goes on day and night. What a wonderful life! Little children pretending to be soldiers. In keeping with tradition, the games will end up being taken terribly seriously."

Ignatz Waghalter, Out of the Ghetto into Freedom, 1936

Fade-out – New Beginning – Synthesis

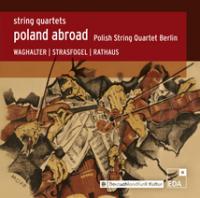

The string quartet genre has already once before been in the spotlight in the Poland Abroad series. With works by Mendelson, Padlewski, and Laks (EDA 34), the focus was on the fate of three Polish composers who became victims of the National Socialists' policy of persecution and annihilation because their life circumstances did not provide a lifeline for flight and exile or, like Padlewski, who joined the resistance. With the present recording, we turn our attention to the works and biographies of three Polish-Jewish musicians who were spared ghetto, concentration camp, and violent death thanks to timely emigration, and who are linked by decisive biographical details. All three were born in Poland at a time in which the Polish state had not yet been reestablished and was a political pawn in the hands of the monarchies of Prussia, Austria, and Russia. All three built careers in Berlin. All three managed to reach a safe harbor in the USA after Hitler's seizure of power, and were active in New York until the end of their lives.

The question of descent, homeland, roots, and identity became an issue for Waghalter, Strasfogel, and Rathaus only as a result of their stigmatization as Jews. For them, exile began not in Germany, but with the departure from Germany, which they perceived as their actual, their spiritual homeland. That what Rathaus wrote in April 1933 – from Paris, the first station of his exile – to his Viennese publisher Hans Heinsheimer could also have been formulated by Waghalter or Strasfogel. In spite of all the differences, the German-Austrian-Polish symbiosis is deeply inscribed in the works of these three composers. This makes them interesting not only from a music-historical perspective. They are, also and precisely due to their outstanding artistic quality, documents of a truly European culture, a culture of dialogue, of interaction, and mutual stimulation.

Ignatz Waghalter was born in 1881 into an impoverished family of musicians in Warsaw as the fifteenth of twenty children. The poverty was due to the circumstance that Waghalter's father was a strict adherent to Jewish ritual, a life style incompatible with the work schedules of professional orchestras. Already at the age of six, Ignacy performed with his siblings at festivities and in the salons of Warsaw's aristocracy. However, the financial means for a professional training were lacking. So in 1898, not yet of legal age, he set off for Berlin, where his outstanding talent was quickly recognized. Recommendations initially led him to Philipp Scharwenka, with whom he studied composition for a while, before Joseph Joachim took him under his wing and helped him obtain a place in the studio of Friedrich Gernsheim at the Prussian Academy of the Arts. Gernsheim imparted in Waghalter the heritage of German romanticism, above all in its classicistic, Brahmsian manifestation, taught him compositional technique and ethos, and gave the youthful-impulsive natural musician a direction and goal. Waghalter's earliest preserved chamber music works – for example, the Violin Sonata op.5, dated 1902, which was awarded the prestigious Mendelssohn Prize of the Prussian Academy of the Arts and the undated String Quartet op.3, presumably composed in 1901 – but also the remarkable Concerto for Violin op.15 from 19101 bear witness to this symbiosis of Slavic exuberance and sophisticated compositional technique so characteristic also of Dvořák. That Waghalter had his op.3 published by Simrock in Leipzig in 1913, at a time in which he was already a luminary in German musical life, shows his high estimation of this early work. A life as a freelance composer in Berlin of the early twentieth century was hardly conceivable for a Polish Jew, and so Waghalter prudently decided to first establish an existence as a conductor, in which he was assisted by no less than Arthur Nikisch. In 1907 he was engaged at the Komische Oper, where his first opera, Der Teufelsweg (The Devil's Path), was premiered in 1911. In 1912 he was appointed first principal conductor at the new Deutsches Opernhaus in Charlottenburg, the predecessor of today's Deutsche Oper, which opened on 7 November 1912 with Beethoven's Fidelio under his baton. He became a close friend of the Opera House's first director Georg Hartmann (the dedicatee of Waghalter's string quartet), with whom he defined the aesthetics and program of the new house, the popular orientation that understood itself as middle-class alternative to the elitist repertoire of the Court Opera, today's Berlin State Opera. Among Waghalter's greatest achievements as music director of the Deutsches Opernhaus undoubtedly include the legendary interpretations of Puccini's operas, which set standards, brought acclaim to the Italian composer who until then had been without luck in Berlin, and paved the way for the further dissemination of his works in Germany. After difficult years during the First World War and the financial failure of the Opera in 1923, Waghalter resigned his positions and emigrated for the first time to New York. There he assumed the direction, as successor to Joseph Stransky, of the New York State Symphony Orchestra, the predecessor of the New York Philharmonic, but, in spite of the offer of a contract renewal, he returned to Germany already in 1925. The purely commercial orientation of American musical life was abhorrent to him. He subsequently composed several operettas, served as general music director of the Ufa film company, conducted as a guest at the Deutsches Opernhaus and at the Opera in Moscow, and directed the National Opera in Riga for a year. Compelled to emigrate again in 1934, he first moved to Czechoslovakia, where he wrote his autobiography Aus dem Ghetto in die Freiheit ("Out of the Ghetto into Freedom"). From there he went to Vienna, where in 1937 he composed his last and still never staged opera Ahasverus und Esther, based on the biblical Purim story (Book of Esther) about the rescue of the Persian Jews, in which he attempted to evoke a positive turn in the looming fate of European Jewry. In advance of the "Anschluss", he left Austria for the USA where the conditions for him, now one of numerous migrants seeking assistance and employment, in no way similar to the luxurious situation of his first New York engagement. In the USA he experienced the racial segregation as a mirror of European anti-Semitism. His plan to establish a classical symphony orchestra made up exclusively of African American musicians was supported by James Weldon Johnson, the most important spokesman of the "Harlem Renaissance". A fervent opponent of fascism and all forms of political reaction, Waghalter declared in a 1939 interview that music "is the citadel of universal democracy". However, with Johnson's death and in the face of ferocious opposition, the orchestra, too, died after only a few appearances. The premiere of Waghalter's New World Suite, composed for the "American Negro Orchestra", was not to take place. Only recently rediscovered in the composer's legacy, the manuscript has been edited and recorded for the first time.2 Waghalter died of a heart attack on 7 April 1949 in New York. None of Waghalter's operas, which were performed with such great success at the Komische Oper and the Deutsches Opernhaus during the 1910s and 20s, have yet found their way back onto the stage. Whereas recent recordings have awakened growing interest in his chamber and orchestral works, the operas and operettas of the "German Puccini", as he was referred to owing to his inexhaustible melodic inventiveness, remain to be rediscovered.

No less vehement was the caesura caused by Hitler's seizure of power in the biography of Ignace Strasfogel (Polish: Ignacy; German: Ignatz),3 who was born in Warsaw in 1909. In 1933, only just twenty-four years old, he was still a dark horse in international musical life, and did not yet have a reputation that could have opened for him a field of activity abroad as a composer. However, the child prodigy, who came to Berlin with his mother following his father's early death in 1912, had already caused sensations a number of times. Initially by the fact that he was accepted, as the youngest regular student at the Berlin College of Music, into Leonid Kreutzer's piano master class at the age of thirteen and, at the age of fourteen, into Franz Schreker's composition master class, two of the Weimar Republic's most prominent talent forges. In 1926, the year of his graduation, he received the Mendelssohn Prize for his Second Piano Sonata, as the youngest composer in the history of this prestigious award. During the 1927/28 season, he accompanied Hungarian star violinist Joseph Szigeti on a world tour; the following season he gave concerts with Carl Flesch. In 1928 he returned again to the Berlin College of Music for graduate studies in conducting with Julius Prüwer. A wise decision, for in exile in New York his stupendous pianistic talent in conjunction with his abilities as a conductor, which he had been able to perfect as répétiteur at the Düsseldorf Opera, the Berlin Staatsoper, and as musical assistant to Max Reinhardt at Berlin's Schauspielhaus, helped him attain a permanent position at the Metropolitan Opera. He was active there – after an interlude as pianist of the New York Philharmonic – from 1951 to 1971 as répétiteur, and from 1957 also as conductor of numerous opera performances. One of his favorite and most important tasks at the Metropolitan Opera was the preparation of the entire cast for the first performances there of Berg's Wozzeck in 1959, a piece that had made a profound impression on him at its world premiere production in Berlin in 1925. In 1974 Strasfogel accepted the position of principal conductor at the Opéra du Rhin in Strasbourg. In 1979, however, he returned to the USA where he dedicated himself to pedagogical work at the Mannes College of Music in New York and at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. Strasfogel left behind early works, which have partly remained unpublished to the present day, and, after decades of silence, a swan song composed in the 1980s and 90s. An actual body of "mature" works (operas, symphonic works, concertos), by means of which a composer of his stature would have attained worldwide fame, is lacking. However, in the case of Strasfogel, one has to be careful with categories such as early and late works. For already the works of the sixteen-year-old display a mastery, a command of compositional craftsmanship, a depth of expression, and a level of reflection that we virtually encounter only in the greats of the first half of the twentieth century. In an impromptu confrontation with the undated First String Quartet, presumably written around 1928, nobody would believe that it is the music of an eighteen- or nineteen-year-old. It occupies a special position within his "early works" in that, in the context of an oeuvre devoted largely to his own instrument, the piano, Strasfogel turned for the first time to the string quartet, a genre that was not "native" to him. Whereas Waghalter's early work with its four-movement structure is entirely obliged to the classical-romantic tradition, the young Strasfogel breaks on the formal level with all conventions by means of the two-movement layout of his quartet. Astonishing for one of Schreker's favorite pupils, who held his teacher in high esteem even into old age, is the stylistic proximity to the Second Viennese School. Nothing is to be heard here of Schreker's impressionistically refined, late-romantic tonal aura. Instead, Strasfogel confidently, and just as unorthodoxly as Berg, makes use of the twelve-tone technique, writes a radical, yet finely nuanced counterpoint, and suspends the prioritization between the main voice and the accompaniment by means of absolute linearity. Pure triads function only as punctuation marks. That which begins as a slow movement (Adagio) becomes increasingly imbued with scherzo elements and ultimately leads into a fugue (Allegro) that is simultaneously a development in which the lyrical opening theme is contrapuntally juxtaposed with two further, sharply contrasting themes. Everything here, crowded into the smallest space, is thematic, and yet the texture is distinctly transparent at all times. The energy that results from the extreme densification of the first movement, in which the tradition remains tangible at most in the "neo-baroque" conception of the themes (head motif as well as fortspinnung or sequencing, respectively), literally erupts in the expansive structure of the second movement. Here we encounter "endless melodies" of a different texture, but of a nature similar to late Schubert: wide arches carried by finely chased rhythmic patterns in the secondary parts that are always also thematic work. Strasfogel shows himself to be avant-garde above all in the emancipation of the melodic lines from the measure-dictated meter – the combination of polytempo and polymeter in the second movement numbers among the most exciting things to be found in the string quartet literature of this epoch.

Karol Rathaus, another of Schreker's favorite pupils, who followed his teacher from Vienna to Berlin in 1920 when Schreker assumed the direction of the Berlin College of Music, numbered among the established names of the German-Austrian music scene in 1933. He received commissions from the Berlin Staatsoper and the Berlin Staatsballett, and was performed by numerous renowned conductors, including Kleiber, Furtwänger, and Jochum. His music for Fedor Ozep's Der Mörder Dimitri Karamasoff (after Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov) from 1930 was considered a milestone of composition for film. Since Karol Rathaus had already left Germany before Hitler's seizure of power and, as an employee of a movie production firm in Paris, did not have the status of an emigrant, he at first remained unaffected by the increasingly stricter immigration policies in France. However, as a result of employment restrictions and quota regulations for foreigners, his economic situation soon deteriorated to such an extent that he accepted an invitation to collaborate on two film productions with prominent casts in London, and moved to England in 1934. After initial successes in England, he found himself in the same situation as before in France. When an engagement as music editor with the BBC failed to come about due to the lack of an English passport, it became clear to him that it was again time to pack his bags. Rathaus placed his hopes on Hollywood and the American film industry. In Hollywood, however, the claims had already been staked out, primarily by the very first emigrants, who set new standards for the genre: Max Steiner had already established himself in the American dream factory in 1929; Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Franz Waxman followed in 1934. The lobby of the American film composers made sure that the newcomers did not skim all the cream off the top. It became increasingly difficult for composers arriving from Europe, even one of Rathaus's stature, to get a foot in the door. Rathaus's odyssey ultimately ended in New York, where he was offered a professorship in composition at the prestigious Queens College.

Also closer to the Second Viennese School than to his teacher Schreker is Karol Rathaus's Fifth String Quartet, his last completed composition, written in 1954 shortly before his death. In the quartet, he worked with Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique in a just as unorthodox manner as Strasfogel, but more consistent than in his Rapsodia Notturna for cello and piano of 1950. This can only be heard by a trained ear. And even someone familiar with Rathaus's oeuvre will not be able to perceive a break between the previously written works and this one. In fact, we find here all the characteristics of the style he developed already in the 1920s: a melancholy lyricism, a subdued expressionism in the abrasiveness of many of the unison passages, typical melodic turns of phrase and rhythmic figures of signature-like character, and above all a strongly narrative gesture that builds up to a dramatic climax. The twelve-tone technique, employed without any systematic compulsion, serves Rathaus for the unification of the material above all in the first two movements, pointing to a strong shared substance through the reference to the same row. Instead of the avoidance of tonal reminiscences, Rathaus on the contrary emphasizes the consonant or mildly dissonant interval constellation by means of the dominance of major and minor thirds in the "thematic" structure of the row. Through the almost continually linear, contrapuntal texture of the movement, the impression of tonality in the conventional sense is however avoided as a matter of principle. The same effect is attained in the third movement by chromatic turns of phrase (that are not gradual but rather erratic fillings of the chromatic space of an interval) and symmetrically formed scales as we know them also in Bartók, among others. Rathaus's last work is not one of resignation: the élan – as the third movement unambiguously shows – is unbroken. It is rather one of synthesis in which the tradition in which one stands and that which one has developed within it is once again reflected and sublimated from an olympian perspective. It is however also one of parting and – like Stefan Zweig's exile work The World of Yesterday – of "a European's" commitment to a world that in 1954 was irretrievable lost.

Frank Harders-Wuthenow

Translation: Howard Weiner, David Waghalter Green (quote from Aus dem Ghetto in die Freiheit)

1 Concerto for violin and orchestra, op.15, Rhapsodie for violin and orchestra, op.9, Sonata for Violin and Piano, op.5, Idyll and Geständnis for violin and piano. Alexander Walker, cond., Irmina Trynkos and Giorgi Latsabidze, soloists. (Naxos)

2 New World Suite, Mandragola: Overture and Intermezzo, Masaryk's Peace March; New Russia State Symphony Orchestra, Alexander Walker, cond. (Naxos)

3 Above all violinist and pianist Kolja Lessing has done much for the rediscovery of Strasfogel as a composer, bringing Strasfogel's original compositions for piano, his art songs, as well as his phenomenal piano transcriptions of Schreker's works back into the concert hall and making premiere recordings.