IX: Hoeller - Bonus: From Five pieces for piano: No. 5

Please select a title to play

I: Hoeller Five pieces for piano (1964)

I: Hoeller Five pieces for piano (1964)I: Hoeller Five pieces for piano (1964)

1 Introduzione - Sostenuto

I: Hoeller Five pieces for piano (1964)

2 Sehr zart, poco rubato

I: Hoeller Five pieces for piano (1964)

3 Sehr energisch, durchaus schroff

I: Hoeller Five pieces for piano (1964)

5 Toccata, in tempo ferreo

II: Hoeller - Diaphonie for 2 pianos (1965)

6 Diaphonie

III: Hoeller - Piano Sonata No. 1 (1968)

7 Sostenuto - Tempo I

III: Hoeller - Piano Sonata No. 1 (1968)

9 Introduzione - molto agitato

IV: Hoeller - Piano sonata No. 2 (1986)

10 Piano Sonata No. 2

V: Partita for2 pianos (1996)

11 Preludio. Andante

V: Partita for2 pianos (1996)

12 Fuga polimetrica. Vivo

V: Partita for2 pianos (1996)

13 Fantasia. Lento

V: Partita for2 pianos (1996)

14 Conductus. In tempo ferreo

V: Partita for2 pianos (1996)

15 Fantasia II. Quasi improvvisando

VI: Hoeller - Piano Sonata No. 3 (2010-11)

17 Piano Sonata No. 3

VII: Hoeller - Doppelspiel for 2 pianos (2009-12)

18 Duoplay

VII: Hoeller - Doppelspiel for 2 pianos (2009-12)

19 Figura ritmica

VII: Hoeller - Doppelspiel for 2 pianos (2009-12)

20 Monument

VII: Hoeller - Doppelspiel for 2 pianos (2009-12)

21 Patterns

VII: Hoeller - Doppelspiel for 2 pianos (2009-12)

22 Ostinato

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

23 Entrée - suono quasi orchestra

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

27 Zwiegespräch

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

28 Artikulation

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

30 Gemäßigter Aufschwung

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

31 Verzweigung

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

32 Tastengeläut

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

33 Elegia giocosa

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

34 Lines and Shadows

VIII: Hoeller - Monogramme (1988-2003)

35 Fluktuation

IX: Hoeller - Bonus: From Five pieces for piano: No. 5

37 No. 5: Toccata, in tempo ferreo

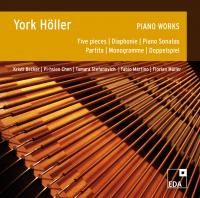

The special role that the piano takes in York Höller’s oeuvre is the result of his life story. As a sixteen-year-old aspiring pianist, he made his debut with one of his own compositions. He supplemented his composition studies under Bernd Alois Zimmermann at the Cologne College of Music with postgraduate piano studies under Alfons Kontarsky, one of the most important interpreters of the avant-garde during the second half of the twentieth century, and to whom he dedicated his First Piano Sonata. The works written between 1964 and 2012 for this instrument not only mark important stages of York Höller’s compositional development, but they also reveal his fundamental interest in – and knowledge of – the playing characteristics of the instrument, which have a direct influence on the structure and facture of the writing: York Höller’s piano works are genuine keyboard music in the tradition of the important piano composers of the past, from Beethoven through Chopin and Liszt to Debussy, Ravel, and Bartók. After a comprehensive overview of the piano oeuvre of the Cologne-resident Krzysztof Meyer (eda 36, Christian Seibert), eda records devotes itself again to the piano works of an important contemporary composer, which are presented nearly complete on this double CD. This is a compilation of recordings that have already appeared in various other places. The piano works that were composed between 1968 and 1996 (5 Pieces for Piano, Diaphony, the First and Second Piano Sonata, the Partita) were issued in 2003 by CPO but have long been out of print. The Third Piano Sonata is from Fabio Martino’s debut CD (Oehms Classics, 2013), which was produced in 2011 following his first prize at the Competition of the Kulturkreises der deutschen Wirtschaft. Monogramme and Doppelspiel, which were both premiered at the Ruhr Piano Festival, were released in 2005 and 2012 within the framework of the respective festival documentation. A historical recording from 1965 of the last of the 5 Piano Pieces, which shows the composer’s exquisite pianistic skills, completes the circle of this fascinating pianistic oeuvre created over the period of nearly a half a century.

Labyrinthine Keyboard Paths

by York Höller

My parents were not professional musicians, but my interest in music and piano playing were awakened quite early by the family – above all by my mother, a good amateur pianist. After having learned my sister’s piano exercises on my own, I received my first piano lessons at the age of ten. Parallel to that I also began to freely improvise on the piano and to write down what I had improvised, that is to say, to “composed.” In my first pieces, I attempted to emulate the style of Mozart. Subsequently, above all Beethoven and Brahms were to become my musical role models.

Modernism soon entered my life in the guise of Paul Hindemith; the Capriccio with which I made my public debut as composer and pianist at the age of sixteen was reminiscent of Hindemith. But the dominant figure during this phase of development was first and foremost Béla Bartók. Through my piano teacher Helmut Zernack, I also became acquainted with Bartók’s Suite op. 14, which I played with enthusiasm, for example at a benefit concert for the UNICEF, alongside one of my own new creations that was very much oriented on Bartók’s style. The reviews spoke of “absolutely promising creative power” and “obligation to study music.” (By the way, I later destroyed all the works written before 1964, which I sort of regret today.)

After high-school graduation, I took up my musical studies in 1963 in Cologne. I earned the money for my own grand piano before the beginning of the first semester as an unskilled laborer on a construction site. Initially, I studied music education and was simultaneously accepted into the piano master class of Prof. Else Schmitz-Gohr (the former teacher of all three Kontarsky brothers), who had herself been trained by the Liszt-pupil James Kwast, and had experienced Busoni, Stravinsky, and other musical greats on the concert stage in Berlin.

I compositionally picked up the thread of Schoenberg and the twelve-tone technique developed by him in 1964 with my Five Pieces for piano, which I premiered myself that same year. These pieces, which I consider to be my actual “opus 1,” are based on a single twelve-tone row (along with inversion, retrograde, retrograde of the inversion, and their transpositions).

In 1965 I attended Pierre Boulez’s analysis seminars as well as the lectures by Theodor W. Adorno and others at the Darmstadt Vacation Courses. As a consequence of my occupation with serialism, which began there, and at the same time as a personal homage to the still highly esteemed Béla Bartók, I wrote Diaphony for two pianos. It evolved from the idea to expand the ten-tone introductory motif from Bartók’s Sonata for two pianos and percussion into a twelve-tone row, to derive from it corresponding series of tone lengths (but not serial dynamics or articulations!), and to musically process them in as diverse a manner as possible. Toward the end of the piece, the Bartók motif is quoted exactly. (During a study sojourn in Paris in 1974/75, I rewrote and revised the musical text.)

After passing my examinations in music education, for which I submitted the thesis “Progress or Dead-end Street? Critical Observations on Early Serialism,” I left my composition and harmony teacher Joachim Blume, a Fortner pupil, and transferred into the composition class of Bernd Alois Zimmermann, with simultaneous studies in electronic music with Herbert Eimert. In addition, I had conducting instruction under Prof. Wolfgang von der Nahmer and continued my piano studies with Alfons Kontarsky, who during my studies premiered my First Piano Sonata, which was dedicated to him.

With my First Piano Sonata (“Sonate informelle”), I attempted to draw compositional conclusions from my occupation with Theodor W. Adorno’s seminal essay “Vers une musique informelle.” This article, in which Adorno’s decisive commitment to “free atonality” and his skepticism, indeed rejection of the different varieties of serialism and indeterminancy is expressed, in many respects opened – it seemed to me – new perspectives for contemporary composition. However, in my opinion, it left several important questions unanswered, namely, for example, that of the large form and its foundation. This theoretical concept was the point of departure for my “Sonate informelle”: from the first to the last tone – and in contrast to Diaphony, which was still oriented on serialism – it is composed in free atonality. Formally, however, it appropriates the dialectical principle of the late Beethoven sonatas. Thus the first movement is based on two very antithetical structures: a rhythmically flexible figure characterized by appoggiaturas and arpeggios and an element of regular tone repetitions. Both formal factors are expanded, shortened, rhythmically stretched, and vertically layered in the course of the movement. In a word: processed in the sense of a “permanent development”.

The slow second movement represents a kind of contemplation of the core interval of the major seventh, which is formative for the whole sonata. This fixed interval is constantly “illuminated” by tones that enter one after the other. At the point of its “saturation,” the chordal field of the first section, which is made up of a number of partial fields, is abruptly interrupted by an agitated, scherzo-like episode. It leads into a strikingly varied reprise of the first section that dies away in the murmurando of low bass figures.

If the second movement is the antithesis of the first, then the third is conceived as a synthesis: as the fusing of formal elements from the first two movements, of moments of the rondo form, the development of the sonata, and the fugal polyphony. This to a certain extent rather intricate process takes place at times against the background of turbulently animated waves of sound that – after transitory phases of calmness – at the conclusion end in the martellato of the lowest bass register attacked in quadruple forte.

In 1969 I wrote a further work for two pianos. It came into being under the critical eyes, so to speak, of Bernd Alois Zimmermann. After his suicide, however, I no longer saw myself in an emotional state to complete it. This fragment remained unfinished for many years. Only in 1984 did I take it up again as a commission for the BBC in London, reworking it as my First Piano Concerto. This two-movement concerto is neither twelve-tone nor serial, but rather composed in a free atonality based on a seven-tone chord. After that I was finished with composition for piano for the time being, because my interest in electronic music had come to the fore – encouraged not least by Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Only in the 1980s did the piano again gain greater importance for my oeuvre. Thus, in 1986, I wrote my Second Piano Sonata. Even though it bears the subtitle “Hommage à Franz Liszt,” it is not a stylistic ingratiation in the sense of neo-romanticism and nostalgia, but rather a composition that attempts to add something distinctive to “great piano playing” through the structural means of modern music. The composition thus refers in a thoroughly ambivalent manner to Franz Liszt, the brilliant pianist, important inspirer, and generous supporter of everything new. From among his many-sided compositional oeuvre, several works, which are considered singular “masterpieces,” stand out. These certainly include the Etudes d’exécution transcendante and several late piano pieces in which impressionistic harmony, bitonality, and indeed atonality are already anticipated: in the seventh and eighth measures of Feux follets from the Etudes is found, for example, a daring “bitonal” figure that – divided between the two hands – consists of the notes G–E–C–A–D-flat–B-flat–F-sharp–E-flat. Out of this “repertoire of tones,” I developed the following structure:

Through the translation of this constellation of tones into corresponding durations of tones (on the basis of the proportion 5:6), a metric and – through the process of projection – formal framework for the whole composition came into being. It accordingly consists of eight sections that are clearly separated from one another in terms of their musical characteristics. Alongside this “germ cell,” which provides the structural unity, two further motifs from Feux follets assume a musical function that goes beyond the often “anecdotal” character of a quotation: the thirty-second–note figure at the beginning, made up of an irregular chromatic scale, and the incisive rhythmic motif in measure 9. In the course of my work, yet another Lisztian element ultimately comes into play: the striking tritone motif from the beginning of the late piano work Unstern (after Baudelaire). All three motifs are processed, combined with one another, etc., in various ways – in a word: “developed.” This “sonata” thus lacks the moment of the “exposition,” which has become formally superfluous, since literally everything is “development,” but one in which “the ear vitally hears in the material what has become of it.” (Adorno, “Vers une musique informelle”). The Second Piano Sonata is dedicated to my partner of many years, Gisela Sewing, who passed away unexpectedly in July 1987.

From this direct personal experience with death arose the need to compose a larger work in the manner of a Requiem. Thus Pensées, the second piano concerto, a half-hour-long, one-movement work in the form of a Requiem, came into being in 1990–92. This concerto moves in new tonal dimensions in as far as it – as the first of its kind – was composed for a midi grand piano to which a digital synthesizer is attached. The pianist operates this synthesizer with his playing and key pressure, whereby the whole thing is controlled by a computer. In contrast to other of my works, a playback tape is used here only at the end; otherwise the described live electronics dominate.

With that I had, as it seemed to me – with regard to my personal sound concepts and experiences – largely exhausted the repertoire of electronic sound production: from analog audiotape electronics up to digital live electronics. For this reason, in the subsequent period I turned again increasingly to pure instrumental composition and in 1996 once again wrote a work for piano, that highly developed instrument to which, in my musical existence, I ultimately felt a deeper connection than to the synthesizer and sampler. Why? Because of my being rooted in that great European musical tradition, ranging from Bach to Ligeti, so closely connected with the piano (and its relatives). But this answer only onesidedly represents the intentions of a composer who for a long time also composed and employed numerous tonal structures and noises beyond the tempered twelve-tone scale and harmonic spectra in the area of electronic and computer music. However, from the very beginning, I seldom invented and elaborated these new kinds of sounds and noises for their own sake, but as a rule with regard to the musical form (or tonal structure).

Here we approach a personal credo: it is made up, among other things, of the conviction that the search for new tonal effects and playing techniques in the area of instrumental music leads more and more to acoustic arbitrariness. It becomes increasingly clear – also in modern physics, for example – that the physical material, thus that which is quantifiable, is increasingly losing importance, while thinking in spiritual-energetic, that is to say, in qualitative categories, seems to be gaining ground. I attempted to express this thought in my Partita for two pianos from 1995 in the following manner: it is based on a twenty-three-tone, spiral-form, open “tonal structure” (not a “row”), whose intervals and immanent harmonies (four chords of 2, 4, 7, and 10 tones, respectively) determine the melodic-harmonic structure of the piece. Through the transmittal of the interval relationships to the meter, “temporal structures” (arrays of measures) emerge, which call forth the different metrical processes in a characteristic manner in the six pieces. The titles of the individual pieces, like the title of the whole cycle, indeed appear to refer to Baroque models, but rather take aim at formal archetypes that should be briefly described: Preludio: an intonation, ornamentation, and alternating illumination of the “germ tone” D; Fuga polimetrica: a framework of tonal and temporal structures strictly related to one another appears asynchronous here; that is to say, shifted by six measures in the second piano with respect to the first; Fantasia I: out of a twenty-three–tone chord (a tonal structure projected entirely in the vertical direction) is developed a kind of “improvisation” on the individual sections of the tonal structure and its intervalic compression, respectively; Conductus: above a ostinato-like repeated return motion of the tonal structure in rigid symmetry, a number of rhythmically independent layers pile up to a complex polyphony; Fantasia II: delicate lines and their “shadows” develop out of the widely dispersed opening tones of the tonal structure; Gigue: repeated, quasi “drummed” triplet figures in breakneck tempo introduce a crazy “pas de deux.” Approximately in the middle, it leads into a quotation from the beginning of “Général Lavine – eccentric,” the bizarre piece in the Préludes that Debussy composed after having been captivated by an appearance by the star dancer Lavine at the Folies Marigny.

The Partita is obliged to the spirit of Johann Sebastian Bach and Claude Debussy, a spirit whose polarity Bernd Alois Zimmermann always encouraged me to blend and to transform. The work is dedicated to Franz Xaver Ohnesorg, who commissioned it for the Ruhr Piano Festival.

The idea to make something in a larger format out of the Partita came to mind already on the evening after the premiere by Elena Bashkirova and Brigitte Engerer. After long deliberation, I came to the conclusion that a three-movement concerto could be formed through the expansion of the Preludio, Improvisation I, and Gigue sections. The result was therefore not merely to be a transcription, but rather a far-reaching transformation and expansion. The outcome was Widerspiel (“Counter-play”) – a concerto for two pianos and orchestra, completed in 1999. The title refers to a fictional letter that Hugo von Hofmannsthal, in the role of Philipp Lord Chandos, published in 1902. This now famous “literature letter” addressed to Francis Bacon, concerns, among other things, the inner form: “the deep, true, inner form that beyond the enclosure of the rhetorical tricks can only be imagined, that of which one can no longer say that it orders the material, for it pervades it, elevates it, and simultaneously creates poetry and truth, a counter-play of eternal powers, magnificent like music and algebra” (Hugo von Hofmannsthal).

Composed between 1995 and 2003, the Monograms for piano, a cycle of fourteen short character pieces, were inspired in some cases by the “round” birthdays of the dedicatees. This series is made up of two groups of seven pieces each, of which the respective first pieces (“Entrée” and “Gemäßigter Aufschwung”) have an introductory function, and of which the respective last pieces (“Frenesie” and “Scanning”) have a concluding or summarizing function. The other pieces, too, correspond musically with one another; for example, the second with the ninth, the third with the tenth, etc. As the subtitles already imply, the pieces are very different in terms of character, structure, and pianistic-technical conception. The structure of some of the pieces (nos. 2, 4, 9, and 11) are derived from the musical note letters contained in the names of the respective dedicatees. The designation Monograms refers particularly to these four pieces. All the other pieces are based on a twenty-two–tone “tonal structure” (which incidentally also – with small modifications – determines the order of the pieces), “temporal structures” derived from it, and the principle of “permanent development,” that is to say, categories that one also knows from other works by me. “Scanning” is a kind of montage of all thirteen preceding pieces.

Whereas all the piano works mentioned up to now are anything but easy to master technically and artistically, I saw myself confronted with a new challenge in Doppelspiel (“Double-play”) for piano four hands. An idea developed by Franz Xaver Ohnesorg, in conjunction with Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Tamara Stefanovich, and proposed to several composers with a view to a project for the Ruhr Piano Festival, involved writing a piano piece for young players that was to be performable both in a two-hand and a four-hand version and not too difficult. In this way, Soloplay for piano two hands, and a four-hand, somewhat enriched variant with the title Duoplay, came into being. Because I had so much fun composing this, I did not want to stop at just one piece, and extended it into a little cycle of five four-hand pieces that could easily be mastered by good young pianists. All the pieces are composed in free atonality.

My Third Piano Sonata was written as a commission for a piano competition sponsored by the Kulturkreis der deutschen Industrie (Cultural Circle of the German Industry). The winner of this competition, the young Brazilian pianist Fabio Martino, premiered it on 9 October 2011 in Essen’s Philharmonie. Like my Second Sonata, the work is in one movement but, with a duration of ca. ten minutes, of smaller format. The pianistic demands, however, are comparable. This is also true of the form that, in turn, is not based on the dualistic principle that characterizes the classical sonata form, but rather on the principle of the “permanent development.” After a calm, freely fashioned, quasi “improvisational” introduction, the first elements of a tonal structure establish themselves at the beginning of the main section (quick tempo) in fast pendulum motions of minor and major seconds. This is made up of a total of thirty notes, divided into four groups of tones of different length out of which result the chords that essentially constitute the piece. Also in the translation of the tonal structure into a temporal structure (arrays of measures), the process resembles that employed in the Parita (see above). The main part is divided into several sections and, analogous to this, passes through various stages of expression. Out of the alternation of the playful-virtuoso and lyrical-restrained moments as well as of the dramatic outbursts and an excessive intensification (toward the end), a form arises in which perhaps something of the “most intensity-rich human world in music,” as Ernst Bloch put it, is expressed, which was and is my primary goal in my works.

Cologne, July 2014