IV: Karol Rathaus – Suite from the ballet "Le Lion amoureux" op. 42b (1936)

Please select a title to play

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

01 Ouverture

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

02 Qui sont ces gens étranges

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

04 Voici par ordre

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

05 Ce sont nos Oles

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

06 Oh, la pauvrette!

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

07 Je vois la vie

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

08 On m'apelle l'hirondelle

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

09 Comme les autres

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

11 Elle aurait

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

13 Et pourquoi pas?

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

15 On m'apelle l'hirondelle

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

16 Où est-elle

I: Simon Laks – L'Hirondelle inattendue (1965)

17 Ah! Laissez moi parler

II: Ferdinand-Louis Bénech / Ernest Dumont – L'Hirondelle du Faubourg (1912)

19 L'Hirondelle du Faubourg

III: Karol Rathaus – Prelude for Orchestra op. 71 (1953)

20 Prelude for Orchestra

IV: Karol Rathaus – Suite from the ballet "Le Lion amoureux" op. 42b (1936)

21 Sarabande

IV: Karol Rathaus – Suite from the ballet "Le Lion amoureux" op. 42b (1936)

22 The Lion's Dance

IV: Karol Rathaus – Suite from the ballet "Le Lion amoureux" op. 42b (1936)

23 The Queen and the Lion

IV: Karol Rathaus – Suite from the ballet "Le Lion amoureux" op. 42b (1936)

24 Dance of the Flower Girl

IV: Karol Rathaus – Suite from the ballet "Le Lion amoureux" op. 42b (1936)

25 Finale

Two Strangers

Simon Laks and Karol Rathaus – two Polish composers of Jewish descent of the same generation, both born around 1900. Two composers whose biographies are exemplary for the fate of Polish music in the first half of the twentieth century.[1] After generations of Polish artists and intellectuals in the nineteenth century were forced into a life in exile because of the political situation in their native country, Laks and Rathaus numbered among the first to choose to live abroad permanently for reasons of better opportunities for artistic development. The former, Laks, a native of Warsaw, felt a stronger affinity, after an intermediate sojourn in Vienna, to the French mentality and achieved fame in the cosmopolitan milieu of the metropolis on the Seine. The latter, Rathaus, a native of Ternopil, which at the time of his birth belonged to Austro-Hungarian Galicia, went to Vienna and then, following his teacher, Franz Schreker, to Berlin. While the clarté and esprit of French neoclassicism became the aesthetic maxim for Laks, Rathaus’s talent developed in the spirit of German late-Romanticism and expressionism. Both carved out careers in their adopted homes, careers that experienced a dramatic caesura after Hitler’s seizure of power. Rathaus managed to flee into exile and survived in New York. A resumption of his career in Germany after 1945 was out of the question. Laks was detained and then deported to Auschwitz in 1941. He survived the Shoah as a member, and later director, of the men’s orchestra in the Auschwitz II–Birkenau extermination camp. For Laks, who in the 1930s had composed for the Roth Quartet, for Maurice Maréchal, Vlado Perlemuter, and the legendary Polish singer Tola Korian, the artistic breakthrough had come too late to establish a position in French musical life on which he could have built on after the war – after deportation, Auschwitz, and forced-labor camp. In spite of occasional successes and awards, he increasingly fell silent as a composer, and from the end of the 1960s until his death, he dedicated himself almost exclusively to literary works. A number of compositions from his pen have only recently received their posthumous premieres.

At the latest with the sensational success of his film score to Fedor Ozep’s legendary 1931 Dostoyevsky screen adaptation The Murderer Dimitri Karamazov, Rathaus made a name for himself beyond Germany.[2] He received commissions from various German orchestras, and conductors such as Furtwängler, Kleiber, and Jochum championed his works. His reputation as a composer of film music brought him prestigious commissions in France even before 1933, so he did not have any difficulties obtaining a visa and work permit. Yet, after Hitler’s seizure of power, life became more complicated for foreign artists in France. The streams of emigrants from Germany intensified an atmosphere of unwelcome competition and resulted in labor law-related restrictions. Rathaus quickly felt the effects of this when after moving to Paris in January 1933 he suddenly earned much less for his film scores than just a few months earlier, and he had to share his fees, even if only for the sake of appearance but to his disadvantage, with French co-composers whom the production companies were forced to hire due to quota regulations. Invitations to prominently cast film productions in England (Broken Blossoms directed by the exile John Brahm, and The Dictator directed by Victor Saville) appeared the way out of a deteriorating material situation. But there, too, the employment opportunities were increasingly affected by bureaucratic chicanery, so that shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, Rathaus finally saw himself compelled to seek an existence for himself and his family in the USA. Rathaus had already artistically treated the subject of exile and self-assertion in a foreign land in his only opera Fremde Erde (“Foreign Soil”), which was premiered by Erich Kleiber on 10 December 1930 in the Berlin State Opera. He, too, a “wandering Jew,” he saw in the subject not only an, in his opinion, necessary, timelessly valid theme for the genre of opera, but also the relevant time reference that the call for “opera of time” (Zeitoper) had so vehemently demanded in the 1920s in order to liberate opera from its museum-like state. It is significant that Rathaus took up the theme of the stranger also in the most important commission he was to receive after leaving Germany, in the ballet music Le Lion amoureux for Colonel Basil’s Russian Ballet Company in the 1937/38 season at London’s Royal Opera House Covent Garden. (The suite was first performed on 13 March 1938 by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Clarence Reynolds.) Even if the adaptation of La Fontaine’s tale concerns the domesticating and ennobling power of love – the aspect of the stranger is even more exaggerated vis-à-vis La Fontaine by the lion’s bursting in on a courtly milieu – the story can also be interpreted with respect to Rathaus’s own biographical situation, which is told as a “subtext” on the level, or by the means, of music. For the correlations lion = atonal = avantgarde and queen/court = tonal music represent musically-symbolically that very shunting off of the composer, who was once a protagonist in the modern music scene in Germany, to a milieu in which his “language” is perceived as irritating and strange. To be sure, this confrontation of styles remains episodic in the suite, and is for the most part limited to the initial tonal imagery of the lion’s entry in the scene, yet in the preface of the score Rathaus himself ascribes to it programmatic importance. It is an indication that in most cases forced exile meant not only a dramatic, often tragically occurring caesura in the artist’s biography, but also resulted in the abandoning of aesthetic positions. However, Rathaus was never a proponent of a hard-line avantgarde, and already at the end of the 1920s had cautioned against provoking a break with the audience and the accompanying ghettoization of contemporary music. In spite of this, there is a good deal of humor and self-irony in the Enamored Lion. Obvious are many dramaturgical as well as stylistic parallels with Schreker’s 1908 dance-pantomime after Oscar Wilde’s The Birthday of the Infanta (EDA 13), which likewise has to do with the intrusion of a stranger – there an ugly dwarf – into a courtly milieu. (The transformation of La Fontaine’s rural world into Rathaus’s courtly milieu may well trace back directly to Schreker/Wilde.) Rathaus, who experienced Schreker’s pantomime (under the new title Spanish Feast) in a production by the Berlin State Opera in 1927, adopted the principle of contrasting neo-Baroque and expressionistic elements as a means of setting to music the antagonism between nature and culture. It is very interesting to see how the semantic connotation of the stylistic layers shifts in keeping with the biographical, music- and contemporary-historical contexts in which the works came into being.

If Rathaus’s suite from the ballet music to The Enamored Lion was the first larger symphonic work with which he introduced himself to the American audience at a concert of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra under Vladimir Golschmann in February 1939, then the Prelude for Orchestra was his last orchestral composition, which he composed as a commission from the Louisville Orchestra and its founder and chief conductor Robert Whitney, and that was premiered on 12 June 1954, barely six months before his death. In a bravura piece, which however eschews any superficial brilliance, Rathaus gives the orchestra’s soloists and the individual sections opportunity to develop their own specific qualities and beauties. Like the Vorspiel zu einer grossen Oper (“Prelude to a Grand Opera”), the last orchestral work by his teacher Franz Schreker, Rathaus’s Prelude also appears to combine within itself, as Rathaus’s biographer Martin Schüssler aptly wrote, “all significant elements of an imagined drama.” Indeed, the piece not only seems like a summarization of Rathaus’s work in a compact space: with his strong contrasts and emotional discharges, the musical dramatist Rathaus, who had no opportunity to write for the stage in the USA (except for the reconstruction of the original version of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov for the Metropolitan Opera), may have envisioned here a sort of overture to an imaginary opera.

“Pour aller plus loin que les astres” – “To go further than to the stars,” wrote Claude Aveline (1901–1992) with a wink of the eye in a presentation copy of his Bestiaire inattendu, which was published in 1959 by the Mercure de France publishing house. And indeed, the interplanetary journey of a society reporter through the expanses of the universe to the paradise of the famous animals leads far beyond the destination. Aveline had already produced this suite of reports about a series of animals from myths and legends several years earlier as radio plays for French Radio (awarded the Prix Italia), and it was in this form that Simon Laks first encountered the material that inspired him to his first and only opera. Claude Aveline, a child of Russian-Jewish emigrants, was a colorful character in French intellectual life since the 1920s. In 1921 he met Anatole France, who made him to one of his closest friends and confidants. He reaped early fame as a poet and as the “youngest publisher in the world,” was active in the Résistance, shined as an essayist, novelist, and author of philosophical crime thrillers, influenced the existentialists, was close to the surrealists, but, as a skeptic and leftist moralist, he did not let himself to be monopolized by any prevailing trend. His poem Portrait de l'Oiseau qui n'existe pas (“The portrait of the bird that does not exist”), which has been translated into numerous languages, provided the stimulus for a series of artistic realizations into the 1970s by a large number of painters from the most diverse stylistic directions (initially as a donation in the Parisian Musée d'Art Moderne, today in Centre Pompidou).

Aveline’s Bestiaire inattendu refers less to the tradition of the myths-parodies of an Offenbach or the modernized myths of a Gide (Prometheus Illbound); rather, the cycle is close to a genre that Franz Blei tried out in a similar manner in several of his miniatures (Andromeda, Three Imaginary Letters), that of the refutation of myths by means of counter statement. In six episodes, the famous animals relate from their point of view the true versions of their stories, which in the legends, as they are told by men, have been stood on their heads or greatly distorted: Jonah’s whale appears, Prometheus’s eagle, Androcles’s lion, the poet Pellisson’s tamed spider, the donkey of the manger story, and, in the tongue-in-cheek epilogue, the “Swallow of the Suburb” that becomes the “Unexpected Swallow” in Laks’s opera.

Laks knew the author since the early 1950s, and already in 1952 had set his Portrait de l'Oiseau qui n'existe pas as a song for voice and piano. He must have recognized in Aveline’s Voltarian intellect a kindred spirit. Both shared a wry, subtle humor and an unclouded view of the “condition humaine,” the one from the experience of the Résistance, the fight against the Nazis in France, the other as a survivor of the Auschwitz extermination camp, where Laks was able to escape death in the gas chambers only “thanks to an endless series of wonders.”

Whoever is acquainted with Ferdinand-Louis Bénech and Ernest Dumont’s chanson L’Hirondelle du Faubourg from 1912, and knows of its great popularity in France, immediately understands the “coup de génie” of Aveline’s story as well as the composer’s inspired intuition for discerning an ideal subject for an opera. The composers’ problem of finding subjects appropriate for opera, which has accompanied the history of the genre and that Franz Schreker once described, in reference to his own situation, as the impossibility “to set a subject in which the fundamental idea is not one that demands the music – no – is the music itself”: here it is solved in an ideal-typical manner, as it were, for the music – the melody – becomes, literally, the theme of the opera. The notorious question of why there has to be singing at all is not raised if a chanson plays the main role. The theme of the stranger – the chanson as “alien element” in the context of the opera – is used by Laks and his congenial librettist Henri Lemarchand (who also translated a series of Laks’s Polish songs into French) for an over-the-top intellectual and witty game with the genre, like that achieved by Richard Strauss in an entirely different form in Ariadne and Capriccio. The apotheosis of the melody, which the reporter strikes up in his aria at the end of the opera, is by all means to be taken literally. For it is the melody in which the immortality potential of the music manifests itself in the highest concentration. “The song is everywhere,” the reporter sums it up, “while we, men and animals, are always only there where we happen to be.” The disdain that the guardians of so-called serious music have for the popular melody – at the time of the composition of the opera, the drifting apart of serious and popular music certainly experienced its absolute zenith in the history of (European) art music – finds its expression in the Hirondelle inattendue in the arrogance with which the animals encounter and reject the scruffy swallow among them as foreign to the species.

Laks experienced the alienation of music through its utilization for the Nazi’s death machinery – his book Music of Another World provides information about this. He experienced being a stranger as an exile before and even more so after the war, the estrangement from his native country, Poland, which was under Communist rule, and ultimately the foreignness as exclusion from the circle of the chosen, i.e., those musicians who after the war belonged to the establishment. In the utopia that appears at the just as cheerful as cryptic conclusion of the opera, the strain of a continuously traumatic life experience presumably also finds relief.

L’Hirondelle inattendue is a work sui generis, a loner in the genre, written without a commission, or perhaps as a commission from a higher place. Laks reflects upon music with the means of music, and strikes up a hymn to its immortality. There is no lack of witty allusions: the attentive listener will recognize old acquaintances such as Schubert’s Trout or Mozart’s “image aria” from the Magic Flute. A reference at an appropriate place to Laks’s contemporary – and bird expert – Olivier Messiaen is hardly to be overheard. The more familiar one becomes with the work, the greater the astonishment at the degree of technical mastery that the score reveals. Laks, who during his lifetime was not to hear even a handful of his orchestral works in performance, proves himself to be a master of instrumentation, and also of the human voice. The opera is literally teeming with affectionate details – beginning with the musical imitation of a wing beat in the first measures – and absolutely impressive is the enormous spectrum of moods and colors that the composer is able to unfold within the narrow space of his one-act opera.

The portals of the theaters have to the present day remained closed to the Hirondelle inattendue. During the composer’s lifetime, it saw merely a musically unsatisfying studio production in 1975 by Polish Television (in a Polish translation). Within the context of what was said above, its exclusion from the repertoire, not to mention from the relevant reference works, is indeed almost consequent. But who knows, perhaps someday the Hirondelle inattendue will be welcomed onto the stages, into the paradise of famous operas ...

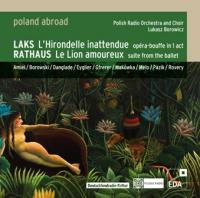

The realization of the present CD production, which for the first time and finally presents the work’s beauties and merits in a proper light, was not without its dramatic moments. It was preceded by the concertante French first performance, initiated by Michel Pastore and funded by the European Commission within the framework of a multiyear European project, at the musique interdites festival on 11 July 2009 in Marseilles, with Marie Laforêt in the title role and a part of the ensemble heard on this recording. The CD production, originally planned for April 2010 at the Warsaw Broadcasting Corporation, fell victim to the airplane catastrophe in Smolensk and the subsequent week of mourning in Poland. Małgorzata Małaszko, director of the music division of Polish Radio; Bogna Kowalska, director of the Radio Orchestra; its artistic director and chief conductor, Łukasz Borowicz; the Polish Radio Choir and its director Małgorzata Orwaska; Piotr Kaminski, who accompanied the rehearsals of the chorus in Krakow and worked on honing its perfect French diction; recording engineers Gabriela Blicharz and Lech Dudzik, who with their artistry make one forget the often difficult acoustical conditions of the live recording; all the participating singers and instrumentalists, as well as Michel Pastore, the director of the musique interdites festival, and Hannelore Brenner-Wonschick, the chairwoman of the affiliated Berlin association Room 28, deserve great thanks for enabling the project to finally be brought to a successful conclusion in June 2010.

The loss of the complete performance material after the Warsaw television production necessitated the preparation of new performance material. The new edition of the opera by the music publishers Boosey & Hawkes Bote & Bock in Berlin was supported by funds from the cultural promotion program of the European Commission and private donations. We would like to thank Winfried Jacobs, the managing director of Boosey & Hawkes in Berlin, for his ongoing support of the edition of Simon Laks’s works, as well as all the colleagues who for years have helped the edition with words and deeds. In particular, Jens Luckwaldt helped with great commitment in the extensive editorial work and design of this booklet. Last but not least, we owe a debt of gratitude to Stefan Lang from Deutschlandradio Kultur, who participated as co-production partner also for this installment of “Poland Abroad.”

Frank Harders-Wuthenow