IV: Alexandre Tansman – Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam (1968–69)

Please select a title to play

I: Grzegorz Fitelberg – The Song of the Falcon (1905)

I: Grzegorz Fitelberg – The Song of the Falcon (1905)I: Grzegorz Fitelberg – The Song of the Falcon (1905)

1 The Falcon – Symphonic Poem after Maxim Gorki's Tale

II: Eugeniusz Morawski – Nevermore (1911)

2 Symphonic Poem after E. A. Poe's The Raven

III: Simon Laks – Poème for Violin and Orchestra (1954)

3 Poème

IV: Alexandre Tansman – Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam (1968–69)

4 Prologue

IV: Alexandre Tansman – Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam (1968–69)

5 Mouvement I. Tempo di toccata

IV: Alexandre Tansman – Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam (1968–69)

6 Mouvement II. Perpétuum mobile

IV: Alexandre Tansman – Hommage à Erasme de Rotterdam (1968–69)

7 Tombeau d'Erasme

The present recording documents the program of a concert given by the Staatsorchester Frankfurt at the "Music Festival on the Oder River" on 12 March 2006, which had as its motto "Weimar Triad – Alternating Musical Currents between Poland, Germany, and France". It was conceived as the thematic continuation of the festival "Poland in the heart – Composing abroad: Polish Composers in Europe 1850–1950", which was organized by Berlin's Konzerthaus in collaboration with the Berlin University of the Arts and DeutschlandRadio Kultur, and that provided the impulse for EDA's new series "Poland Abroad". The festival in Berlin – the first concert series in Germany devoted exclusively to Polish music – understood itself as a homage within the framework of the festivities for the eastward enlargement of the European Union in May 2004. The concert in Frankfurt (Oder) also had a festive background. To be commemorated, corresponding to the time and place, were a series of anniversaries of symbolic importance not only for German-Polish relations: the hundredth anniversary of the foundation concerts of the group "Young Poland in Music" around Karol Szymanowski in 1906–7 in Warsaw and Berlin, which marks the actual hour of birth of the modern era of Polish music; the 500th birthday of the Viadrina University, the former cradle of European humanism in the German-Polish border city of Frankfurt an der Oder; the fifteenth anniversary of its reestablishment as the Viadrina European University in July 1991, as well as the fifteenth anniversary of the "Weimar Triangle", the trilateral league initiated on 28 August 1991, Goethe's birthday, by the three then incumbent foreign ministers of Poland, France, and Germany, and which since 1998 has also been active at the level of the heads of state and government.

As a consequence of Poland's political history there is also, and above all, in musical history an intensive triangular constellation, and with it numerous concrete points of contact for the comprehension and carrying forward of a "mutual historical tradition", as stated in the program formulated by the founding fathers of the "Weimar Triangle". Impeded in the development of an independent national culture after the loss of its national sovereignty at the third partition of Poland in 1795, generations of Polish intellectuals and artists saw themselves forced to develop their talents abroad. The most important role was played in this by the cultural centers of Germany and France – Berlin and Paris. Later, during the time of National Socialist persecution, the lines of escape stretched further, to England and above all to the USA. With the series "Poland abroad", EDA intends to look into these aspects of Polish musical history as well as into the hitherto unexamined consequences of the Shoah for Polish musical life. The present studio production, made immediately following the concert in Frankfurt, is devoted to a series of key works by Polish composers of the first half of the twentieth century.[1] These are key works less in the sense of any long-lasting, concrete music-historical influence, which remained denied to them for various reasons – these performances represented the world premiere of Laks' Poème and the German premieres of both Tansman's Hommage and Morawski's Nevermore; these are key works rather in the sense of their symbolic meaning within the framework of a yet to be written European musical history that does not ignore the aspects of exile and Shoah.

Grzegorz Fitelberg (1879–1953) numbers among the outstanding figures of Polish musical life in the first half of the twentieth century. As an internationally renowned conductor[2] and founder of an important group of composers, he exerted a strong influence on the development of Polish music. Fitelberg was born into a Jewish family in Dünaburg (today in Latvia). From 1891–96 he studied at the Warsaw Music Institute in the violin studio of the Tchaikovsky-pupil Stanisław Barcewicz and composition with Berlin-trained Zygmunt Noskowski, who in the period between 1881–1909 taught most of the outstanding Polish composers of the next generation. Fitelberg initially worked as a violinist in the Warsaw opera orchestra, and from 1901 in the orchestra of the newly founded Warsaw Philharmonie, which played a decisive part in the late upsurge of Polish symphonic music after 1900. Starting in 1904, he appeared as conductor with this orchestra, whose music director he was from 1909–11 and again from 1924–35. In between he was active at the Vienna Court Opera, in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Paris, among other places. From 1934–39, he directed the newly established Symphony Orchestra of the Polish Radio in Warsaw, from 1947 the Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice. During the Second World War, he lived as an emigrant in South America and the USA.

Grzegorz Fitelberg was active as a composer only until around 1914. His small oeuvre contains primarily orchestral and chamber music as well as art songs. Early on he was able to gain the patronage of the Polish prince Władysław Lubomirski, who himself entertained ambitions as a composer. In 1905, together with three other Noskowski pupils (Ludomir Różycki, Karol Szymanowski, and Apolinary Szeluto), Fitelberg founded the "Young Polish Composers' Publishing Company", which was financially supported by Lubomirski. This group of composers, which became known in Poland as "Młoda Polska w muzyce" ("Young Poland in the Music"), gave two spectacular symphony orchestra concerts in both Warsaw and Berlin in 1906–07. Premiered under Fitelberg's direction were a series of orchestral works with which the group desired to define their aesthetic position in the sense of a secession. The modernistic gesture of these works provoked a fierce controversy in the Polish press between the adherents of a conservative concept of a Polish national music and those sympathetic to the new direction, the latter orienting themselves musically on Richard Strauss and, with regard to content, on Poland's contemporary symbolistic literature (the so-called "Młoda Polska"). The group's first concerts on 6 February 1906 in Warsaw and 30 March in Berlin went down in Polish musical history as the beginning of a new epoch.

Fitelberg's symphonic poem The Song of the Falcon received its premiere at the Warsaw concert and was also played in Berlin. The work is based on an episode from the short story of the same name (1895) by the Russian author Maxim Gorki, in which a mortally wounded falcon tells a snake of the fascination of flying and of freedom. It is not difficult to project the image of the suffering falcon onto Poland's political situation in 1906, and to see in it the severely wounded Polish nation, whose pride is nevertheless not to be broken, surrounded by snakes. However, Fitelberg's Song of the Falcon does not belong to the category of the descriptive symphony, such as one knows, for example, from Richard Strauss' symphonic poems. Fitelberg also abstains from all manner of concrete or even enciphered patriotic statement such as can frequently be found in the contemporary Polish symphony. Fitelberg seems to have been inspired above all by the dialogical situation of the antagonistic figures in Gorki's story, which provides the thematic material for a formal construction obliged, if anything, to absolute music. The Song of the Falcon captivates by means of the very sophisticated and original treatment of the orchestral forces. However, the piece gains its music-historical importance from the paradigmatic formulation of a standpoint important for Polish music after the turn of the century, a standpoint that marked a successful amalgamation – i.e., not one that exhausted itself in eclecticism – of Russian and new-German influences. Fitelberg undoubtedly shows himself in this context and at this point of time to be the group's greatest compositional talent in the area of orchestral music.

Eugeniusz Morawski[3] (1876–1948) was in a completely different respect one of the key figures in the development of Polish musical life in the first half of the twentieth century. Like Fitelberg and Szymanowski, he numbered among the composers who came out of Noskowski's studio at the Warsaw Music Institute and, inspired by Richard Strauss, initially turned to the symphonic poem. Besides attending the Music Institute (1899–1904), the son of a highly placed Warsaw public official (Arkadiusz Dąbrowa-Morawski, whose family tree goes back in a direct line to the princes Radziwiłł) also enrolled in the Warsaw School of Fine Arts where he formed a friendship with his Lithuanian composer colleague Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, who was likewise an artist. As a member of a fighting unit of the Socialist Party of Poland, Morawski was incarcerated in November 1907 in the Warsaw Citadel for agitation against the Russian occupation and sentenced to four years in Siberia. His father, himself a veteran of the 1863 uprising, sold the family's possessions and used the proceeds to ransom his son from the Russian authorities. The sentence of banishment was reduced to exile. Morawski went to Paris, earned his living as a pianist, completed his composition studies as a pupil of the legendary contrapuntalist André Gédalge at the Conservatoire, and enrolled as a painter and sculptor in the Académie Julien. In Paris he became friends with Paderewski and Artur Rubinstein (who mentioned Morawski repeatedly in the first volume of his memoirs), and it was there that Morawski's most important works came into being in the 1910s and 20s. He experienced his breakthrough as a composer on 9 June 1910 with the premiere, which he conducted himself, of the symphonic poem Vae Victis in Paris' Salle Gaveau. That same year followed the premiere in Monte Carlo of the symphonic poem Don Quixote, and a year later of Les Fleurs du Mal in Angers. Morawski quickly reaped recognition in his homeland, too. Don Quixote experienced its Polish first performance already in February of 1912 in Lvov, followed two months later by the first performance in Warsaw. Even after the recovery of Poland’s independence, Morawski remained in Paris, and only in 1930 accepted the appointment as director of the Posen Conservatory. In 1932, he was commissioned with the reorganization of the Warsaw Conservatory, as a result of which he became entangled in the controversies concerning the ultimately unsuccessful attempt to establish, under Szymanowski's direction, a national academy of music superior in rank to the Conservatory. Morawski raised the standards at the Conservatory to the highest possible level within a short time[4] and was confirmed in his position until the occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany in 1939. After the occupation, he was offered the continued direction of the Conservatory under German supervision, which he however declined, organizing instead the operation of an illegal underground college.

Morawski was the founder and chairman of the "Société des Artistes polonais" in Paris. Besides his function as college president, he held a series of important offices in Polish cultural life during the 1930s. He was, among other things, co-founder and chairman of the Fryderyk Chopin Institute, deputy chairman of the Polish Composers Society, chairman of the League for the Protection of the Polish Press, and chairman of the art commission of the Warsaw Opera. Moreover, he represented the Ministry of Culture on the jury of both the Wieniawski as well as the Chopin Competitions. Morawski did not need these posts for his own interests and advantage. Since he promoted neither the performance of his works nor their dissemination by means of publication, he had to experience how the better part of his oeuvre was irretrievably lost with the destruction of his apartment during the suppression of the Warsaw uprising in the late summer of 1944: four operas, three symphonies, three symphonic poems (Vae Victis, Les Fleurs du Mal, Prometheus), five ballet scores, eight piano sonatas, and seven string quartets fell victim to the flames. Three symphonic poems (Nevermore[5] and Ulalume after Poe, and Don Quixote) could be rescued, as were a string quartet, an early piano trio dedicated to Čiurlionis, several art songs, and the ballet music to Miłość ("Love") and Świtezianka, which was honored in 1933 with the Prize of the City of Warsaw as an "exceptional phenomenon in Polish music".

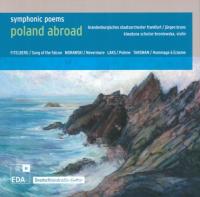

The conflict with Szymanowski within the college's administration, but above all with the supporters of Szymanowski's cause, proved in the long run to be fatal for the reception of Morawski and his music, for in the second half of the twentieth century – in the course of Szymanowski's belated recognition as the central figure of Polish music – he was almost only perceived as Szymanowski's adversary. "To acknowledge the position due to Morawski is to the present day felt to be a breach of faith, a betrayal of Szymanowski", opined Władysław Malinowski in 1979 in the first appraisal of Morawski, thirty years after his death, in the music journal Ruch Muzyczny.[6] While the works of other Polish composers of that generation are performed at least occasionally, Morawski's surviving oeuvre nearly fell into oblivion. The present recording is the first ever CD production of a work by Morawski. With the reproduction on the cover of this CD of one of the few oil paintings by Morawski that were not destroyed, the artist Morawski is also commemorated for the first time. Poles who are familiar with the subject point out that Morawski's instrumentation method has become very popular,[7] and so it might be a small comfort that his artistry lives on, in a manner of speaking, in the works of his pupils, among whom are some of the most important in post-war Polish history: Witold Lutosławski, Grażyna Bacewicz, Andrzej Panufnik, and Antoni Szałowski, to mention only a few names also known in the West. Completely impoverished, Morawski died in 1948 as a result of health problems caused by the deprivations during the war. The new, communistic government denied him a position in the rebuilding of Poland's musical life. Morawski was certainly not the right person to occasionally write a "song for the masses or a piece for wind band", as was suggested to him by the new chairman of the Polish Composers Association.[8]

Nevermore was composed in 1911[9] in Paris. The performance on 18 May 1924 in the Warsaw Philharmonie may have been the world premiere; possible earlier performances have as yet to be ascertained due to the very fragmentary documentation as a result of the war.[10] Like Fitelberg's Song of the Falcon, the literary program of this work is based on the symbolic figure of a bird – the ideas for which the birds stand, however, could not be more different. In Poe's poem The Raven, which was published in 1845 and is considered not only one of the most important lyrical texts of nineteenth-century American literature, but in Baudelaire's translation also had a great influence on French modernism, the protagonist – the lyrical "I" – is haunted at night by an uncanny raven. "Nevermore", the only word with which this bird of misfortune again and again answers the protagonist’s insisting questions refers to the irretrievable loss of the protagonist’s lady-love, Leonore. If the sublime aspect of fate comes to life in the image of the falcon, the raven embodies its nocturnal, fatalistic, and ghostly-menacing side – Morawski's setting leads to the depths of a distraught soul.

Morawski composed the psychological protocol, so to speak, of his protagonist, and within the narrowest temporal space experienced with him chilling dread, depths of desperation, but also moments of bliss in the memories of his lady-love. As a Polish composer living in France, Morawski was an advocate of the expressive, late-Romantic style of Mahler, Strauss, and Schoenberg, which helps to explain his isolation in the musical world of his time. Except for several direct correspondences with the text – for example, the onomatopoetic imitation of the knocking sound by means of striking the strings with the bow-stick – Morawski develops a musical representation that detaches itself from the poetic model. The composition is made up of three large sections of which each is informed by new thematic material that is combined with the thematic material of the preceding sections in an increasingly complex polyphony of, to some extent, conflicting associations and feelings. Nevermore certainly numbers among the most idiosyncratic and expressive orchestral works not only in Poland, but also on an international level. One can scarcely resist the fascination of this music, its dark maelstrom. Władysław Malinowski rightly stated that the destruction of Morawski's works in 1944 was "certainly the largest such loss to strike Polish music in both World Wars". And one can only agree with Jerzy Kukla, who places Morawski alongside Szymanowski and Koffler in the rank of "forerunners of the then modern in Polish music".

Vae Victis, the prophetic title of one of Morawski's symphonic poems that were burned during the war, could just as well also be the motto of Simon Laks' life and work. The composer, who following studies in Vilna and Warsaw lived in Paris from 1926, had started out on a promising career when he was deported first to the Pithiviers transit camp near Orléans, and then on 17 July 1942 to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau extermination camp. Laks survived the German death machinery primarily because of the fact that he was a musician, which meant that he belonged to the "chosen", as Primo Levi called them in his account of survival in Auschwitz Se questo è un uomo ("If this is a man" [also published under the title "Survival in Auschwitz"]), in contrast to the "damned", those, that is to say, who were not sent immediately into the gas chambers, or who sooner or later died of exhaustion and emaciation in the forced-labor brigades. Laks recorded the time in Auschwitz for posterity in his 1948 book Musique d'un autre monde,[11] an important literary account of the Holocaust and a major source on the role of music in the German concentration camps. In Germany, Laks was for a long time ignored completely both as a witness to the Shoah and as a composer. In the countries in which the book finds and has found an audience, the musician disappeared into the shadows cast by the chronicler, all the more so since it has only been in the past few years that efforts have been undertaken to publish Laks' works.

It is understandable and obvious that the experience of Auschwitz represented an absolute break in Laks' composing.[12] Not only in view of the fact that the experience of the complete reevaluation of all values – Laks referred to Auschwitz as "a sort of negative of the world from which we were abducted" – made the return to a "status ante" impossible. In contrast to Adorno, who, firstly, thought it no longer possible to write poetry "after Auschwitz", and secondly – on the basis of music-aesthetic and music-historical considerations – believed the use of folkloristic materials in art music to be futile, for Laks, who saw with his own eyes the destruction of the Polish-Jewish culture, and himself escaped it only "like through a miracle", the compositional occupation with poetry written after Auschwitz and with folkloristic material of the Polish and Jewish traditions played a central role after the liberation. After the liberation, because before the war Laks "definitely belonged to the group of assimulated Jews who had broken with the religion and the tradition, like his two favorite poets, his compatriots Julian Tuwim and Antoni Słonimski".[13] After the war, Laks thus composed the Third String Quartet "sur des motifs populaires polonais"[14] (1945) and the Ballade pour piano en l’honneur de F. Chopin[15] (1949) with references to Polish or Jewish culture and to the Shoah, but above all a series of art songs: the Huit chants populaires juifs (1948), the Élégie sur les villages juifs[16] (Antoni Słonimski), Pogrzeb/Les Funérailles (M. Jastrum), and songs on texts of his fellow sufferer in Auschwitz, Ludwik Żuk-Skarszewski. The Poème for Violin and Orchestra also belongs in this context, even if no explicit reference is made in the title. It was written in 1954 during a phase of convalescence after a long hospital stay necessitated by the aftereffects of the deprivations experienced in the concentration camp. Within the composer's catalogue it represents an exception in as far as it was the only orchestral work composed without an immediate prospect of a performance: music as a means of reflection, but also as a means of artistic and, not least, of technical self-ascertainment – it was Laks' first orchestral composition after his deportation. Both aspects clearly come to light in the character of the work.

The title "Poème" and the setting for a solo instrument and orchestra speak for an interpretation of the piece as a sort of vocal scene without words. Conspicuous is the unusual structure of this one-movement work that combines aspects of the divergent formal concepts of concerto, suite, sonata-allegro form, and fugue. Introduced successively after the lyrical introduction, the animated second theme – which in the middle of the work is first developed in free counterpoint, then as a fugue – is transformed by Laks, after a mazurka episode before the recapitulation, nearly imperceptibly into a funeral march. In the slow tempo and through an expressive upbeat of a seventh, it losses its dramatic character and reveals its relationship to the elegiac theme of the beginning into which it leads back – and thus into the recapitulation – again in a nearly imperceptibly manner. It is obvious that with this piece, as well as in his first piece written after the war, the Third String Quartet, Laks, a master of irony and understatement, composed a homage to devastated Poland. With the funeral march for a mazurka, he expressed more than he could have done in large-scale symphonies and oratorios.

Alexandre Tansman has time and again been described by his contemporaries as a humanistic personality – in terms of his encyclopedic knowledge, his extraordinary language skills, and his savoir-vivre, above all, however, because of his inexhaustible willingness to help and his human integrity (Henri Dutilleux wrote of Tansman's "exceptionelles qualités humaines", i.e., "exceptional human qualities").[17] It is hardly astonishing, then, that the City of Rotterdam awarded him – the Paris-based Pole of Jewish descent, who had been a French citizen since 1937 – the undoubtedly most prestigious composition commission in its history: a work in honor of Erasmus of Rotterdam’s 500th birthday on 27 October 1969. At this point of time, Tansman himself could look back upon exactly fifty years of an extraordinary career as a composer, pianist, and conductor. Born in Lodz (like his friend Artur Rubinstein), Tansmann won in 1919 the newly established Polish state composition prize under spectacular circumstances: he was not only awarded the first prize, but also the second and third prizes for other works submitted under pseudonyms![18] Tansman, who had studied law and philosophy in Warsaw, then went to Paris, the European musical metropolis, to perfect his skills. Befriended by Ravel and introduced into avant-garde circles, he soon became acquainted with the most important musical personalities and authors of the day. He maintained close, life-long friendships with many, in particular with Stravinsky; Tansman was incidentally one of Stravinsky's first biographers (1948). At the beginning of the 1920s, Tansman joined together with the Czech Martinů, the Romanian Mihalovici, the Hungarian Harsanyi, and the Russian Tcherepnin to form a group of emphatically Eurocentric composers that went down in musical history as the "École de Paris". Having himself already earned an international reputation, Tansman assisted an entire generation of young Polish composers, who, following his example, came to Paris to study, and who – like Simon Laks – organized themselves in 1926 into the "Association des Jeunes Musiciens polonais" ("Association of Young Polish Musicians"). If one desires to fathom the secret of Tansman's extraordinary success – the international musical scene literally lay at his feet from the mid 1920s onward – the key possibly lies in the phenomenon of successful synthesis. A synthesis not only in the balancing of innovation and tradition – the iconoclastic attitude of his composer friends of the "Groupe des Six", for example, that to all intents and purposes he himself also embraced, never became an end in itself for him; where he borrowed from jazz – and hardly a composer of the time did so as systematically as Tansman – this took place parallel to the development of rhythmic models that he found in the traditional Polish folk music. But a synthesis above all in the combination of the most differing, indeed divergent national attributes in the sense of the suspension of thesis and antithesis in a new, higher quality that lends his music its universal character.

Tansman survived the Second World War with his family in exile in California thanks to a visa that could be obtained in 1941 as the result of a petition submitted to the American immigration authorities by Charles Chaplin (the dedicatee of his Second Piano Concerto), Arturo Toscanini, Jascha Heifetz, Eugene Ormandy, Sergey Koussevitsky, and other artist friends of Tansman's who were active in the United States. The fame that Tansman enjoyed at this time in the United States – he had undertaken a first concert tour of America in 1927 as soloist in his Second Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Koussevitsky – can be seen by way of example from his Fifth Symphony, which was given its world premiere in 1943 by the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, performed that same year by the orchestras of New York, Baltimore, San Francisco, and Cincinnati under the direction of the composer, and by 1949 had experienced fifty performances throughout the world under such well-known conductors as Mitropoulos, Ormandy, Koussevitsky, Golschman, Kletzki, and Kubelik.

When Tansman received the commission for a homage to Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1968 his enormous symphonic oeuvre was already nearly completed. With an over seventy-year-old composer who could look back upon an impressive life's work, and who no longer had to prove anything to anybody, one might have expected – also, and exactly, in view of the occasion and the person to be honored – a mild and serene, perhaps also festive late work. Tansman, however, understood the commission more in the sense of an interpretation of that which Erasmus advocated and which is not to be attained through reflection and meditation alone. The idea of an oscillation between the poles "vita activa" and "vita contemplative" may stand as the idea behind the four-movement work, and on this abstract plane a timeless and fundamental understanding of humanistic consciousness and action is reflected in the Hommage à Erasme, rather than the portrait of a concrete person of European intellectual history sketched in music. The work's only festive music in the actual sense of the word, a "Fanfare-Chorale" for brass and percussion that can optionally be placed at the beginning of the work, was composed after the rest of the piece at the request of the commissioning organization as salutatory music for Queen Juliane, who attended the premiere in Rotterdam on 8 February 1970 together with the royal family. In the unconventional sequence of two slow outer movements and two quick inner movements, the four movements of the Hommage astonish, on the other hand, with an almost ascetic austerity that dispenses with extrinsic effects in the two slow movements, and with a rigorous impulsiveness in the quick movements. Nothing in this music seems to look backwards – commemorating – unless in the sense of a reflection on a musical language, developed in fifty years of successful composing, that consistently continued to be developed with regard to the subject. Instead of composing a work of program music about Erasmus, the characteristics of his personality, episodes from his life, or his works in the sense of a descriptive realism, Tansman honored the humanist by means of the transformation of his name into musical material out of which the work emerges, like out of a germ cell or a genetic code: Tansman spelled Erasme, simultaneously using the musical alphabet employed in Poland (and also in German-speaking countries) and the Latin solmization syllables usual in the Romance countries, as E (e) – R (Re = d) – A – S (Si = b) – M (Mi = e) – E (e), which find employment in their diatonic and chromatic readings (re = d and d-flat, etc.) The Goethean idea of a unity of character, biography, and works – "molded form that develops live" – thus finds itself reflected in the composition; the name Erasme not only became the program in the ideal, but also in the literal sense.

I would like to thank the Staatsorchester Frankfurt and its manager Christoph Caesar, who let themselves in for the adventure of a program with entirely unknown music, some of it never before performed; the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation for its financial support of the concert; DeutschlandRadio Kultur for the ongoing dedicated cooperation; Marcin Gmys for numerous suggestions, above all for the encouragement to look into Eugeniusz Morawski; Tomasz Morawski for making it possible to examine the saved portions of his uncle’s estate and for the use of pictorial material; Jerzy Kukla for numerous pieces of sometimes difficult to find information about Morawski's life and works; Gérald Hugon; Mireille and Marianne Tansman; André Laks; but above all Piotr Moss, Joseph Herter, and Antoni Buchner, who provided indispensable help on the voyage of discovery to Poland’s hidden musical treasures.

[1] EDA's first CD within the framework of Poland Abroad: Music for string orchestra, with the Berlin Kammersymphonie under the direction of Jürgen Bruns (EDA 26), documents works by Mieczysław Karłowicz, Simon Laks, Alexandre Tansman, and Jerzy Fitelberg, the son of Grzegorz Fitelberg who is portrayed on the present CD.

[2] Grzegorz Fitelberg conducted the world premieres and also numerous national first performances of most of the orchestral compositions of his friend Karol Szymanowski (he was also involved in the instrumentation of some of them), and forcefully championed his contemporaries. He conducted, among other things, the premiere of Stravinsky's Mavra in Paris in 1922, Lutosławski’s Symphonic Variations (Cracow, 1939) and First Symphony (Katowice, 1948), as well as the Polish premieres of Stravinsky’s Petrushka and Histoire du Soldat, Prokofiev's Symphonie classique, Honegger's Pacific 231, and Weill's Violin Concerto.

[3] Since information on Morawski's life and works is not readily available, except in a few scattered Polish publications – for some incomprehensible reason, the short entry on Morawski was excised from the new, expanded edition of the standard German music encyclopedia Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG) – we have allowed ourselves to go into more detail here.

[4] "In spite of the tension between him and Karol Szymanowski, Morawski proved himself to be an outstanding organizer, pedagogue, and champion of Szymanowski’s works. Morawski improved the prevailing conditions in the Conservatory, established a musicology department, founded three school orchestras, expanded the composition class, endowed an opera studio and chamber ensembles, acquired additional financing for the school, and restored the school’s former high standard of instruction." Polish Biographical Dictionary of the Polish Academy of the Sciences, vol. 21 (1976), p. 71 ff.

[5] The score of Nevermore, which was likewise destroyed in the fire, was reconstructed after the war by Kiesewetter from the only surviving set of parts.

[6] Władysław Malinowski, "Eugeniusz Morawski – not there", Ruch Muzyczny 10 (May 1979).

[7] Morawski's instrumentation method, which was ready for publication at the outbreak of the Second World War, burned together with the scores of his works. Interestingly, Morawski taught only instrumentation and orchestration at the Conservatory, but not composition.

[8] Cited after Jerzy Kukla, "Eugeniusz Morawski – a forgotten or deprecated composer", Ruch Muzyczny 14 and 15 (2 and 16 July 1989).

[9] The sources are contradictory; 1914 is also documented as the year of composition.

[10] Grzegorz Fitelberg also conducted works by Morawski subsequently: for example, Ulalume on 28 May 1929 at a festival of Polish music in Posen with the Orchestra of the Warsaw Philharmonie and, on 1 April 1930 with the same orchestra in Warsaw, excerpts from the ballet Miłość ("Love").

[11] At American universities, this book, in the English translation Music of Another World, belongs to the standard literature on the Holocaust. A German edition, published only in 1998 under the title Musik in Auschwitz, is already out of print. The second edition (2004) of the French version, published by Les Editions du Cerf, Paris, is available.

[12] Those who are interested might want to listen, by way of illustration, to Laks' Sinfonietta pour cordes from 1936, which is obliged to French neoclassicism and documented on EDA 26 Poland Abroad – Music for string orchestra.

[13] André Laks in the epilogue to Mélodies d'Auschwitz (Paris, 2004), p. 152.

[14] See the work commentary by A. Buchner at www.boosey.com/Laks.

[15] Laks also won prizes for his compositions after the war, including at the national Polish Composition Competition 1946 for his Third String Quartet, at the Chopin Competition 1949 for his piano ballade Hommage à Chopin, and in 1965 the Grand Prix de la Reine Elisabeth in Brussels for his Fourth String Quartet.

[16] Laks' songs numbered and number among his most frequently presented works, and are also performed regularly in Poland. Recordings of the Élégie and the Huit chants are to be issued in 2007 on the EDA label.

[17] Mireille Tansman Zanuttini, Gerald Hugon (ed.), Alexander Tansman: Une voie Lyrique dans un siècle bouleversé (Paris, 2005), p. 438.

[18] A memorable record that was matched in 1959 by Krzystof Penderecki.