VI: Berthold Tuercke – Spurengesang (2004)

Please select a title to play

I: Isao Matsushita – Atoll II (1982)

I: Isao Matsushita – Atoll II (1982)I: Isao Matsushita – Atoll II (1982)

1 Atoll II

II: Franz Riemer – Reigen (1985)

2 Mäßig

II: Franz Riemer – Reigen (1985)

4 Allegro giocoso

II: Franz Riemer – Reigen (1985)

5 Cantabile

II: Franz Riemer – Reigen (1985)

6 Sehr frei

III: Dietrich Erdmann – Akzente A (1989/2003)

10 Allegro con fuoco

III: Dietrich Erdmann – Akzente A (1989/2003)

11 Adagio espressivo

III: Dietrich Erdmann – Akzente A (1989/2003)

12 Presto grotesco

IV: Ulrich Krieger – Rote Erde (1992)

13 Rote Erde

V: Rainer Rubbert – deadline (2004)

14 deadline

VI: Berthold Tuercke – Spurengesang (2004)

15 Spurengesang

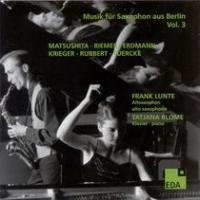

In Berlin of the 1930s an attempt was undertaken to come to terms with the saxophone as a "classical" instrument. Broken off because of repression and war, it found its continuation only in the 1980s. This CD forms the conclusion of a three-part series that presents compositions for alto saxophone and piano from Berlin. The series begins with the year 1930 and continues to the compositional events of the beginning of the twenty-first century. Vol. 1 (EDA 21) and vol. 2 (EDA 22) cover the 1930s (1930–32 and 1934–38, respectively), with vol. 3 devoted to music written since 1982, whereby the most recent compositions are dedicated to the duo Frank Lunte and Tatjana Blome.

The National Socialists put a stop to the development of the classical saxophone that had begun so promisingly in Berlin in the 1930s. Gustav Bumcke (1876–1963), the great pioneer of the classical saxophone in Berlin and founder of Germany's first saxophone class, was not able to continue his teaching activities at Stern's Conservatory after 1936. In that year the authorities renamed it the "Konservatorium der Reichshauptstadt" [Conservatory of the German Capital], and demanded that Bumcke join the Nazi party, which he refused to do. The virtuoso Sigurd Raschèr (1907–2001), for whom nearly all the classical saxophone works of the 1930s had been composed, emigrated via Denmark and Sweden to the USA. Many composers, who had been enthusiastic about the new instrument in its new tonal guise, were persecuted, driven out of the country, conscripted into the military, or banned from practicing their occupation.

The regime's view of the saxophone, which had been classified as "degenerate", had meanwhile become more pragmatic. Thus, in the bands of the German Air Force, one had a predilection for "spirited" saxophone pieces which had been introduced already in 1935 at the instigation of the Inspector of Bands, Prof. Hans Felix Husadel. The Air Force's pilots, who were considered especially daring, were to be kept in the right mood by the "hot" music. The hypocrisy of the regime is also shown by a bizarre directive issued by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels in 1940 in which he ordered the establishment of a swing orchestra, in which saxophones naturally had to be included. "Charlie and his Orchestra" played American hits, whose reworded English texts were laced with German propaganda. The goal was to reach English-speaking listeners in enemy countries with familiar swing music in order to win them over to the National Socialist cause. Goebbels' directive could not even be blocked by the bitter opposition of the "Kampfbund für die Deutsche Kultur" [Action Group for the German Culture], whose director Alfred Rosenberg was of the opinion that one should convert the enemy through German march and folk music. Last, but not least, the poster for the National Socialist "Entartete Musik" [Degenerate Music] exhibition of 1938, with a saxophone-playing, colored dance musician with a Star of David on his lapel (an allusion to Ernst Krenek's opera Johnny spielt auf [Johnny Strikes Up]), reveals the National Socialists' perfidious as well as ambivalent view of the saxophone.

In civilian musical life, on the other hand, the public boycott of the instrument continued. Because of zealous spies at dance events, the musicians were forced to disguise their instruments as specially formed metal clarinets. Many switched over to other instruments, and German saxophone manufacturers soon experienced marketing problems. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Ministry of Education and Propaganda looked into the problem and rehabilitated the saxophone, however only for "good", that is to say "German" music. Through the rehabilitation, the saxophone was once again an official musical instrument, although with a limited range of application. After the war this state of affairs at first continued, even if no longer by edict. An equal status and, as a result, a permanent place in the classical symphony orchestra was in any case out of the question: too few composers made use of the saxophone. If, however, one was required, the part was usually performed by a saxophone-playing clarinetist.

For this reason, classically oriented saxophone instruction in the colleges and conservatories was nearly superfluous; there was no serious need for it. Saxophone students finished school and went directly into dance, popular or wind bands. Most of them played in the Philharmonic Wind Band Berlin in which there were no less than twelve saxophones. In addition, the Radio Berlin Dance Orchestra (RBT), which was reestablished already in 1945, became one of the main employers of musicians in the post-war days. Swing entered the city, not only through the great RBT-Orchestra. Jazz and dance bands shot up like mushrooms and were a part of the economic miracle, just like the VW Beetle. Yet the public did not just have a desire for uncontrolled and uncensored entertainment – after two decades of increasing subjugation of the arts, the people had an enormous need also, and in particular, for classical music.

The saxophone, however, missed the connection during this atmosphere of awakening; the stigma of the disreputable and forbidden surrounding it was still too strong. In the area of classical music, it remained of marginal importance, in popular music it sparkled like it had in the 1920s. A woman in the chorus of Berlin's male-dominated saxophone scene defied this state of affairs: Ingrid Larssen (1913–2001), Gustav Bumcke's daughter and pupil, dedicated herself to the classical repertoire and played since the end of the 1930s as a soloist at all German radio stations. The premieres of her father's works were reserved for her, and she recorded the Sonata (1938) and the Saxophone Concerto (1957), among other pieces, for the radio. In spite of a thirty-year-long musical career, she was not able to bring about a reevaluation of the classical saxophone.

After the establishment of the two German states in 1949 and the partition of Berlin, all the musical training institutions were found in the west part of the city. The Ministry of Education of the German Democratic Republic therefore decided to establish a new college of music in the east sector, which was founded in 1950 as the Deutsche Hochschule für Musik [German College of Music], and renamed the Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler [College of Music Hanns Eisler] in 1964. Only from 1962 was saxophone instruction offered in the department of dance and popular music; the instructor was Horst Oltersdorf (1912–1991). Like Ingrid Larssen, and nearly of the same age, he appeared as a soloist, recording, among other things, Alexander Glazunov's Saxophone Concerto with the Rundfunkorchester Berlin, and playing concerts throughout the GDR.

Meanwhile, at the College of Music in West Berlin, the saxophone department became more and more desolate. At the end of the 1960s, there was only a single student still enrolled. In 1970, Omar Lamparter (*1917), formerly first alto saxophone in the RBT Orchestra, started rebuilding the saxophone class. He was the first instructor since Gustav Bumcke to champion a well-grounded classical saxophone training and to teach the appropriate literature, from solos through quartets to concertos. In 1978 he accepted Detlef Bensmann (*1958) into his class. Bensmann soon made his debut as a soloist and began an international career. Bensmann teaches at the University of the Arts and at the College of Music Hanns Eisler. Two works on this CD were dedicated to him. Also a dedicatee of one of the works recorded here is Johannes Ernst (*1963), who studied in Berlin with Heinz von Hermann and in Bordeaux with Jean-Marie Londeix. He is internationally respected as a soloist, chamber music partner, orchestra musician, and guest instructor, and teaches at the University of the Arts as well as at the College of Music Hanns Eisler. Both musicians have fundamentally changed the standing of the classical saxophone in Berlin. Their pedagogical commitment at the colleges of music contributes to making the history of the instrument in Germany accessible to the up-and-coming generations, and to its reappraisal.

The saxophone is again at home in Berlin, and is observed with interest by audiences and composers. Since the 1980s, numerous works have been composed in Berlin in close collaboration with concert saxophonists – this CD presents a selection for the formation of alto saxophone and piano. Japanese composer Isao Matsushita, born in Tokyo in 1951, came to West Berlin in 1979 with a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and studied at the College of the Arts with Isang Yun. He soon established an artistic friendship with saxophonist Detlef Bensmann, which led to the founding of the "Kochi Ensemble" in order to make Asiatic music more accessible to European audiences. In the course of mutual improvisations, the first sketches were made for a saxophone quartet and a duo for alto saxophone and piano, both of which Matsushita completed in 1982. "Picking up on the idea of Atoll I for saxophone quartet, Atoll II is based on the image of the sea – in particular, of an atoll, depicting the motions of various sounds – that flows together in the saxophone and piano. Beginning with repeated notes, which embody the atoll, the piece consists of five sections. Each of these elements is introduced at the beginning. These individual elements flow along on colored waves of chords, come to the fore, and are swallowed up one after the other. In order to get to know the beauty of the coral atolls that I wanted to bring to life musically, I visited Mago Island in the South Pacific, which is surrounded by coral reefs. Overwhelmed by the deep blue of the sea and the beauty of the flowers in their natural environment, I took a quick glance at the rigor mortis of the ocean. The way of life of the people there, who are hardly influenced by modern civilization and are in perfect harmony with nature, made it painfully clear to me how difficult it is to reconcile the mutually contradictory concepts of development and preservation – and naturally, the fragility of modern civilization."

Franz Riemer was born in Bamberg in 1953. He studied music education along with composing and conducting in Detmold, and musicology together with history and art history in West Berlin. He lived In Berlin until 1987, working as a teacher in public schools and music schools, and was active as a freelance composer, writer on music, choir director, and freelance collaborator at Berlin's RIAS broadcasting company. Riemer composed Reigen [Round Dance] "after a concert with contemporary piano music in which my Five Aphorisms were premiered. A young saxophonist, Johannes Ernst, approached me and asked if I wouldn't like to write a piece for saxophone and piano. Since I used to play saxophone myself, I thought I knew enough about it and agreed to write something for him. From Johannes Ernst's young, but very well-grounded and competent experience and knowledge I received a whole bunch of tips concerning the technical possibilities of the saxophone, and decided to take advantage of all of them. The idea for Reigen came – as so often – as a by-product of something essential. Just then I was reading Schnitzler's Liebelei [Little Affair] in an edition in which it was followed immediately by Reigen. After I had finished reading Liebelei, I read Reigen, too – after all, I had purchased the whole book. I was impressed there by the possibility of allowing two persons – that is to say, characters – to play with one another. With that the formal musical structure was immediately clear: Two (as a rule, completely different) characters (musical themes) meet, approach one another (up to a coupling), and separate again. Each musical section consists of the meeting of two themes. The one theme appears again (in modified form, if necessary) in the next section and meets yet another theme, and so on. In the depiction of the characters in the first three sections I followed Schnitzler's model, but then deviated from it and increasingly interpreted the characters in a purely musical manner. Schnitzler's clear model therefore becomes blurred (for example, Riemer has eight sections rather than Schnitzler's ten), even though the round dance, in accordance with its definition, logically comes back around to the beginning at the end of the piece – here again analogous to Schnitzler's model."

A bridge between the 1930s and Berlin's present musical scene is the life and work of the composer Dietrich Erdmann. Born in Bonn in 1917, Erdmann moved in 1925 with his family to Berlin, where he has lived ever since. Early exposure to the arts came through the pictures of his mother's first husband, August Macke, the painter who was killed in action in 1914. Starting in 1931, Erdmann attended courses with Paul Hindemith, Ernst-Lothar von Knorr, Harald Genzmer, and Hans Boettcher at the "Städtische Volks- und Jugendmusikschule" [Municipal Elementary and Youth Music School]. From 1934 to 1938 he studied with Kurt Thomas, Walter Gmeindl, and later with Paul Höffer at the Berlin College of Music. Erdmann was personally acquainted with some of the composers who composed for the saxophone in the 1930s, including Knorr, Wolfgang Jacobi, and Paul Dessau. In 1935, together with others of a like mind, Erdmann founded the "Arbeitskreis für Neue Musik" [Working Group for New Music] under whose auspices works were performed that did not conform to the prevalent doctrine: an activity that the National Socialists kept under close surveillance, and that at times put Erdmann in difficult situations. From 1938 to the end of the war, he had to do military service. His father, Lothar Erdmann, who was a socialist, was murdered in 1939 in the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. After being released from a Czech prisoner-of-war camp, Erdmann quickly integrated himself in Berlin's musical life, taught at the Pedagogical College, undertook there the setting up of the music department and assumed its direction, was appointed professor in 1954, and dean in 1970. In 1963 he founded the "Studio Neue Musik" [Studio for New Music], in 1972 the "Working Group for Chamber Music". From 1980 until his retirement two years later, he taught at the Berlin College of the Arts. Dietrich Erdmann has received numerous honors, including the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1987, the Stamitz Prize in 1988, the Humboldt Plaque in 1998, and, in 2002 in Wroclaw, the Silesian Culture Prize.

To be sure, Erdmann became acquainted with the saxophone already in the 1930s, yet his first work for the instrument was written only in 1984: Resonances, composed as a commission from the Raschèr Saxophone Quartet. All eight compositions that followed he dedicated to Detlef Bensmann or ensembles whose members came from Bensmann's college class. Akzente A [Accents A] for Alto Saxophone and Piano is based on the composition Akzente for Tenor Saxophone and Piano from 1989. The first of the work's three movements (Allegro con fuoco) distinguishes itself in the piano introduction through rhythmic turbulence, which is the basic trait of the two outer movements. Driven as if by an invisible power, the flow of the music rushes vehemently toward its goal. Already after a few beats, the usual accentuation of the plain three-four meter is no longer perceptible. Before the first movement ends with wild cascades of triplets, it is interrupted by a meno mosso that with its slender, withdrawn introspection prepares the way for the "storm" that is to break out. Whereas the first movement is of a dramatic-turbulent character, the Adagio espressivo receives a predominantly lyrical-melancholy coloring. Trill ornaments lead repeatedly into descending or ascending sevenths; the composer gives both instruments plenty of opportunity to stand out soloistically. In this middle movement it becomes clear how uninfluenced Erdmann is by fashionable trends. In the cheerful, buoyant Presto grotesco – as already in the first movement – Erdmann's deep admiration for Bartók is discernible. The main theme in the piano, introduced in staccato, always follows a comprehensible melody shape, yet without being harmonically anchored. The rhythmic-dynamic slap-tongue in the saxophone is later caricatured with the performance marking "lachend" [laughing], and thus points to the "dangers of overuse" of instrument-specific effects; it reflects a compositional style that makes an effort to remain close to the audience, and is not written for a vacuum.

For composer and saxophonist Ulrich Krieger (born 1962), who has lived in Berlin since 1983, an innovative compositional approach to his instrument is of particular importance. On the basis of a profound knowledge of the tonal characteristics and possibilities, he microscopically breaks down border areas and simultaneously explores the tonal counterparts of additional instruments. "The title Rote Erde [Red Earth] refers to the vast, reddish, Australian desert landscape, whereby the atmosphere is captured in a free, that is to say, non-descriptive manner. It is a pure sound piece. The saxophone part is influenced by the didjeridoo playing techniques of the Australian Aborigines. In a certain sense, it is a sort of anti-saxophone piece, since it contains none of the typical finger virtuosity. The saxophonist plays a single multiphonic fingering through almost the whole piece. All variations on this fingering/timbre are created by very subtle changes of the embouchure and the breathing – another, new sort of virtuosity of tonal fashioning that makes new demands on the performer. The piano part is for "inside piano". It, too, is limited to a single tone (in various octaves) and its minute tonal variations: different sorts of overtones are created in that one strokes the string with diverse materials and varying pressure."

The catalogue of works by Rainer Rubbert, who was born in Erlangen in 1957 and now lives in Berlin, contains numerous pieces for saxophone. The compositions were written in close collaboration with the saxophonists Ulrich Krieger, Johannes Ernst, Detlef Bensmann, and Frank Lunte, and range from bass saxophone solos through chamber music and saxophone orchestra to saxophone concertos. Rubbert sees the use of experimental sounds – such as preparations in the piano or unconventional playing techniques on the saxophone – as formative elements that do not however preclude concertante playing. In deadline, this compositional idea has as its basis a piano chord on contra B-flat that is placed at the beginning and not yet defined in terms of its mode. During the course of the piece, this chord is always distorted in the same manner, it experiences in a contrapuntal manner lasting alterations by means of variations of timbre, be it a scraping of the appropriate string that confirms the ground tone, be it an overtone bell sound of the fifth, f, be it minor seconds in metallic repetition surrounding it, or entirely abstract percussive events. The chord, which at the beginning is in a state of uncertainty as to its mode, receives with the first note of the saxophone a minor third breathed into it, a disposition that constantly permeates deadline and evokes a continual calling into question of that which was heard before. This questioning is provoked not least by the disciplined bustle of six short intermezzos in the form of mutually instigated chases that, based on a pithy, jazz-like main motif, bring about a powerful climax in the middle of the piece. In terms of the structural form, two cadenzas are noteworthy – purifying reminiscences of the compositional material, as it were – and this in two directions: if in the first the listener draws strength for an imminent unleashing, so to speak, the second – stating the main motif in retrograde – steers toward the last of the six intermezzos and anticipates the urging finale.

Through his composition studies in the USA with Rudolf Kolisch, Felix Greissle, and Leonard Stein, Berthold Tuercke, born in Berlin in 1957, stands in the line of succession to Arnold Schoenberg. From 1988 to 1995 he taught harmony and music theory at the Berlin College of the Arts, and initiated various musical projects with his pupils, among whom were also the performers on this CD. This intensive collaboration led to diverse compositions for saxophone, always in the context of a close examination of the possibilities of formal shaping in literature and in theatre – a musical language upon which Tuercke bases most of his works. "SPURENGESANG [Song of traces] is a music of emotional and spiritual chasms that open to him who searches for them in order to make sure of himself. The music circles around the beginning of Ernst Bloch's cycle of thoughts Spuren ("Traces"), just as a mesh of thoughts is developed circularly here:

ZUVOR [Before]

What now? I am. But I do not have myself. That is why we are yet to be.

ZU WENIG [Too little]

One is alone with oneself. Together with the others, most are also without themselves. One must escape from both.

SCHLAFEN [Sleeping]

On our own, we are still empty. We therefore fall asleep easily when the external stimuli are lacking. Soft pillows, darkness, quiet allow us to fall asleep; the body darkens. If one lays awake during the night, it is not at all a state of being awake, but rather stubborn, devouring crawling in place. One notices then how uncomfortable it is with nothing but oneself.

LANG GEZOGEN [Long drawn-out]

Waiting is also dull. But it is also intoxicating. Whoever stares for a long time at the door through which he expects someone can become intoxicated. Like from monotonous singing that drags on and on. Darkness, where it drags to; probably to nothing good. ...

IMMER DARIN [Always in it]

We cannot be alone for long. One cannot put up with it; it is too creepy in one's all too own cabin. ...

Bloch's sparse and yet siren-like narrative style, like notes out of a Kafkaesque diary of one's mental state, plummets us into a chasm in that he un-says the said and says the un-said. In this way, the zero axis of human self-certainty, the universal point of departure of thinking and feeling, is drawn as a darkroom in which all that embraces spirit and soul lies in wait when the two mutually penetrate one another for the sake of their understanding. This whole beginning lies under the music like a sort of sub-text. In each of its moments, it is like a sort of transformation into sound of all that which resonates between the lines. The underlined passages are spoken in the composition, and in each case the other musician simultaneously speaks the words in the reverse order so that the understandability of the text seems to be shifted to that huge, haunted crossing with which the stimulated thoughts find their way to one another in the state of suspense."

This CD with works by Berlin composers from the years 1982 to 2004 concludes the series "Music for Saxophone from Berlin".

Frank Lunte and Tatjana Blome, February 2005